Separation is a difficult time for parents, even those who “consciously uncouple” like Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin. The emotional trauma of separation becomes significantly more challenging, however, when the legal consequences of separation steer parents toward conflict in court rather than compromise out of court.

Separation is a difficult time for parents, even those who “consciously uncouple” like Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin. The emotional trauma of separation becomes significantly more challenging, however, when the legal consequences of separation steer parents toward conflict in court rather than compromise out of court.

In this three-part article, I’m going to talk about how a child’s relationship with a parent can break down when parents separate, and the theory of parental alienation syndrome that tries to explain the breakdown of the parent-child relationship. In Part Two, I’ll talk about what happens to allegations of parental alienation in court and how cases of parental alienation can be distinguished from The courts weren’t fond of parental alienation syndrome as alienation was often difficult to establish as fact and the recommended solution, removing the child from the home of the favoured parent, seemed drastic and at odds with the child’s expressed preferences.situations in which children are justifiably estranged from a parent. In the last part, I’ll talk about the legal and therapeutic options that are available when allegations of alienation are proven.

Parental alienation “syndrome”

Our court system is adversarial. Although processes are in place to promote settlement, if separated parents can’t agree on how they’ll care for the children, they’ll wind up fighting each other to get the result they each think best. This sort of competition encourages parents to take extreme positions, and makes extreme positions difficult to back down from for fear of looking weak or losing face. The stakes, of course, are astronomically high when what a couple is arguing about is their children. With emotions running high, it’s easy to forget how important it is that the children maintain a positive, loving relationship with each parent and that children’s exposure to their parents’ conflict is limited.

In the early 1980s, psychologists began to notice that some children of separated parents developed an alignment with one parent, and a rejection of the other, that was so strong it resulted in the child refusing to visit the rejected parent and became a factor in the litigation. In Surviving the Breakup, prominent American psychologists Judith Wallerstein and Joan Kelly wrote about certain self-absorbed parents and vulnerable older children who “waged battle” together in an “unholy alliance” to hurt the other parent. Five years later, in an article called “Recent Trends in Divorce and Custody Litigation,” psychologist Richard Gardner used the term “parental alienation syndrome” to describe cases of alignment in which children not only engaged in a “campaign of denigration” against the other parent but were actually prepared to reject their relationship with that parent altogether. Gardner believed that such extreme alignments were caused by the efforts of one parent, usually the mother, to indoctrinate the children against the other parent, usually the father.

Gardner’s parental alienation syndrome quickly became a flashpoint of controversy. Men’s rights groups loved the theory because most of the parents said to engage in alienation were mothers; women’s groups loathed it as it seemed to downplay the impact of family violence on children’s interests and preferences. Psychologists were skeptical because:

- there was so little good research on alienation;

- the theory didn’t meet the scientific criteria to be labeled as a diagnosable “syndrome,”; and

- it seemed overly simplistic and was frequently misapplied in court.

The courts weren’t fond of parental alienation syndrome as alienation was often difficult to establish as fact and the recommended solution, removing the child from the home of the favoured parent, seemed drastic and at odds with the child’s expressed preferences.

In 1997, Deirdre Rand, another psychologist, wrote in “The Spectrum of Parental Alienation Syndrome” that parental alienation syndromeIn the early 1980s, psychologists began to notice that some children of separated parents developed an alignment with one parent, and a rejection of the other, that was so strong it resulted in the child refusing to visit the rejected parent and became a factor in the litigation. is a risk whenever parents go to court about a custody dispute She said that the risk of alienation increases: when one or both parents make claims that attack the integrity, moral fitness, or character of the other parent; when the parent seen as responsible for the breakdown of the relationship becomes involved in a new relationship shortly after separation; and, when a parent leaves the relationship suddenly, with little or no warning.

Drawing on work by James Garbarino, Edna Guttman and Janis Wilson Seeley in The Psychologically Battered Child, Rand described five types of parental behaviour that are hallmarks of parental alienation syndrome:

- Rejecting: The favoured parent rejects the child’s need for a relationship with both parents. The child fears abandonment and rejection by the favoured parent if he or she expresses positive feelings about the rejected parent.

- Terrorizing: The favoured parent bullies the child into being terrified of the rejected parent, and punishes the child if he or she expresses positive feelings about the rejected parent.

- Ignoring: The favoured parent withholds love and attention if the child expresses positive feelings about the rejected parent.

- Isolating: The favoured parent prevents the child from participating in normal social activities with the rejected parent and that parent’s friends and family.

- Corrupting: The favoured parent encourages the child to lie and be aggressive toward the rejected parent. In very serious cases, the favoured parent recruits the child to assist in tricks and manipulative behaviour intended to harm the rejected parent.

As a family law lawyer, two other behaviours have also struck me as indications that the alienation of a child is a risk:

6. Distracting: The favoured parent sets up activities, goals or interests which conflict with the other parent’s time with the child, such as enrolling the child in a sports team and placing such a high value on the child’s participation that the child is upset to miss a game or practice to spend time with the rejected parent.

7. Resigning: The favoured parent stops accepting responsibility for the child’s time with the rejected parent, and leaves it up to the child to decide whether to spend time with the rejected parent or not. This puts the child in a loyalty bind by forcing the child to make the choice to see the rejected parent, knowing that the favoured parent doesn’t want the child to go at all.

Alienation, or justified estrangement?

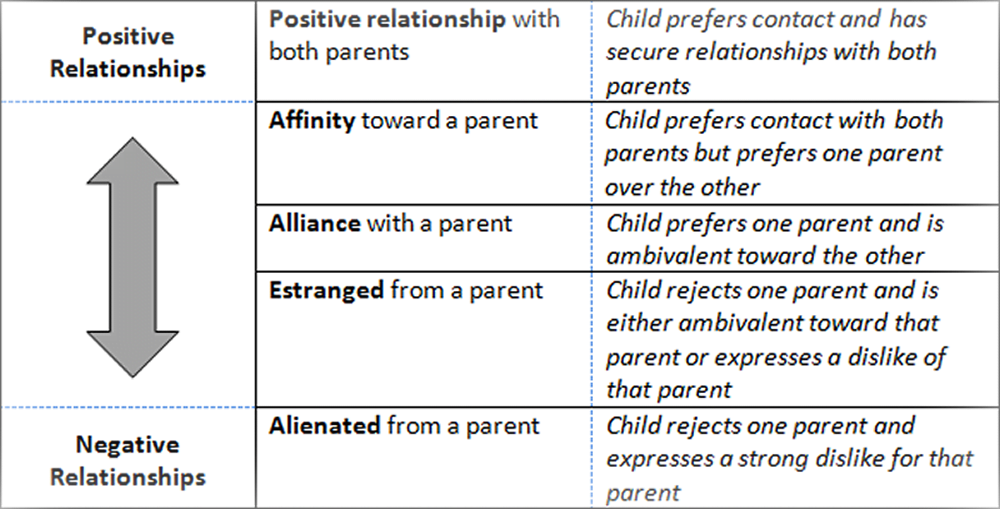

Many parents frankly find it easier to blame the other parent as the cause of the breakdown of their relationship with the children than to find fault within. However, although parental alienation is often claimed, it’s not often established.In 2001, however, Joan Kelly and Janet Johnston published an important article in Family Court Review called “The Alienated Child: A Reformulation of Parental Alienation Syndrome” that focused more on the alienated child than the alienating parent. In their view, parent-child relationships can break down for reasons not involving the malicious interference of the favoured parent and can be described on a scale of quality between positive and secure on one hand and negative and alienated on the other:

Kelly and Johnston recognized that there may be objectively valid reasons for the breakdown of a child’s relationship with a parent, reasons that might actually justify the child’s rejection of and refusal to visit that parent, such as:

- the child witnessing or experiencing family violence at the hands of the rejected parent;

- the rejected parent having a rigid or authoritarian approach to discipline;

- the rejected parent displaying inconsistent and unpredictable expectations and behaviour;

- the immaturity and self-centredness of the rejected parent;

- the rejected parent being emotionally unavailable to the child; or,

- the rejected parent having problems with substance abuse impairing his or her parenting capacity.

All these things might cause a child to become estranged from a parent, rather than being alienated from the parent as a result of the favoured parent’s efforts to poison the parent-child relationship. In such cases, they wrote, children also typically wish to severely limit contact with the rejected parent, and their estrangement from that parent is “reasoned, adaptive, self-distancing and protective.”

The problem, of course, is that certain groups remain smitten with Gardner’s original theory of parental alienation syndrome and it can be terribly easy, and rather tempting, to mistake cases of estrangement for cases of alienation. Many parents frankly find it easier to blame the other parent as the cause of the breakdown of their relationship with the children than to find fault within. However, although parental alienation is often claimed, it’s not often established.

In the next part of this article, I’ll talk about what happens to allegations of alienation in court and how cases of parental alienation can be distinguished from situations in which children are justifiably estranged from a parent.