At some point in high school, we learn that we live in a nomocracy, which is a fancy ten-cent word for a society governed by the rule of law. The whole “governed by the rule of law” thing is an especially important quality of democracies like ours. It includes the following rights:

- the right to vote, and the right to be governed by those whom we elect rather than by monarchs or oligarchs,

- the right to freedom of speech, regardless of what the government thinks of the things we choose to say,

- the right to freedom of assembly, even for purposes of which our government disapproves,

- the right to have a judiciary which is theoretically and actually independent of the legislature and the executive branch,

- the right to be subject only to laws that are published and accessible,

- the right of access to the court system, and

- the right to be free from arbitrary detention.

All of this sounds pretty good. I even think we are getting most of this right in Canada, although we certainly have not reached perfection. We are fairly good with our freedoms of speech and assembly, and many of the other rights affirmed by the Charter. We manage to transition between elected governments without rioting and anarchy. Our judges make their decisions largely without being measured by the partisan yardstick tormenting their American cousins. And the legislation to which we are subject is readily available for review by anyone with an internet connection.

While we might be doing well with the top-level governance issues listed above, we are not doing nearly as well with the lower-level things that affect Canadians’ day-to-day interactions with the state and the courts. Sure, our legislation is published and freely accessible to anyone with a library card. But the majority of these laws are almost incomprehensible to anyone who struggles to read above a grade ten level, and to many of those who do not. We do not do a very good job of talking about the justice system in school. The language of the law is the language of judges and lawyers rather than that of the average person. And I am fairly certain that even the most basic legal concepts not covered by Law & Order are a mystery to the majority of us.

The truth, I’m afraid, is that although every one of us has access to the law and the courts in a formal sense, we do not have access to the law and the courts in a functional, practical sense, any more than having the keys to a car means we can actually drive that car.

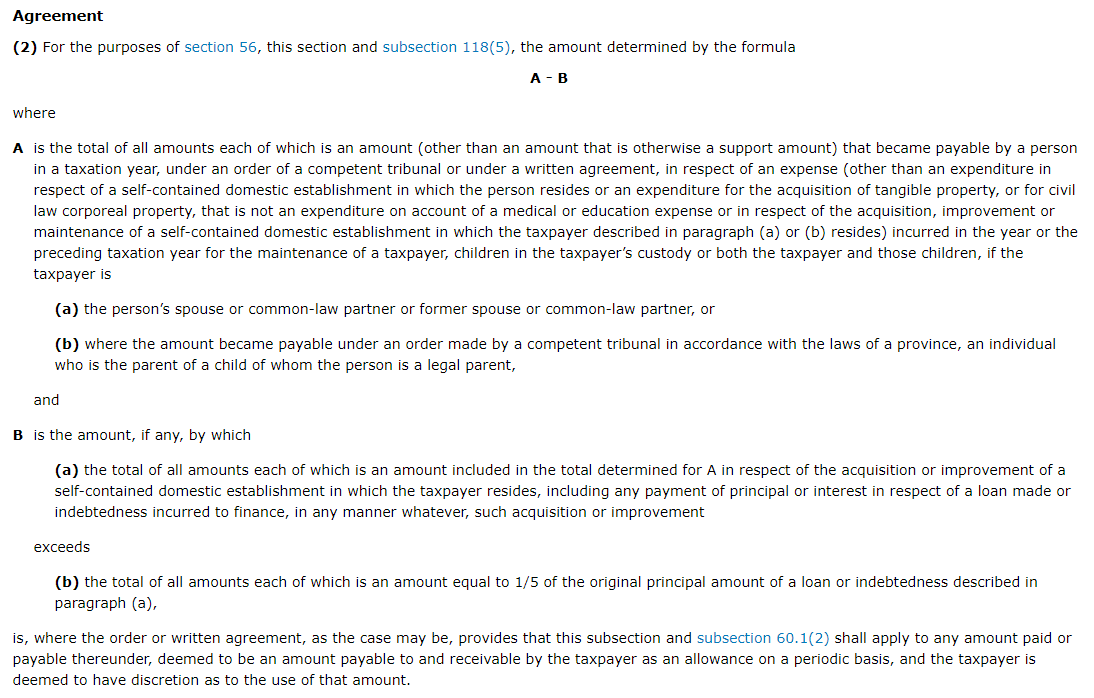

Take, for example, section 56.1(2) of the federal Income Tax Act. This section tells you how to calculate the amounts you need to deduct from or add to your taxable income as a result of paying or receiving spousal support:

Now, I admit to cherry-picking a particularly nasty part of the Income Tax Act for the purposes of this discussion. But I will point out that errors in calculating one’s personal income tax obligations can carry potentially serious penal and financial consequences. You can be sure that the CEOs of neither H&R Block nor QuickTax are going to pay the penalty for you if you muck up your tax calculations. And this is why public legal education programs are so very, very important: they fill a critical gap between the formal access to justice we all enjoy in theory, and the practical ability of individual Canadians to meaningfully access justice in their daily lives. If you need to understand the tax impacts of spousal support and cannot afford to pay a lawyer, which is hardly uncommon, you will likely find yourself visiting a public legal education program.

The language of the law is the language of judges and lawyers rather than that of the average person.

None of these programs are perfect, of course. They cannot cover every area of law in every jurisdiction in Canada. Specialized programs focus on specific areas of the law or specific legal issues, such as the rights of Indigenous peoples, the criminal law, landlord and tenant disputes or commercial law. They cannot address those areas or issues in a way that is comprehensive, written in easy-to-understand language, broadly available, and published in many languages. (My public legal education book, JP Boyd on Family Law, for example, runs to some 789 pages in print yet still provides only a thumbnail sketch of all that is involved in family law in B.C.!) These programs nonetheless provide a critical part of the social infrastructure necessary to ensure that the rule of law is more than a hollow promise.

The shame of it all is that public legal education programs are, at least in Canada, poorly supported by governments and the courts, and even more poorly funded. Personally, I see the obligation to ensure that all Canadians enjoy the benefits of living in a nomocracy as falling primarily on governments rather than on not-for-profit societies which must beg for their budgets each year. If government cannot draft laws and the rules of court in a clear and comprehensible manner, then public legal education programs are what we are left with to fill the gap between theory and reality. I just wish we were prepared to provide them with the funding they deserve.

We need to, I think, increase the legal literacy of our population by radically improving how we teach civics in primary and secondary school if practical access to justice is to become a reality. We also need to make government, the law and the courts as accessible as possible by reducing complexity, ensuring that the legislation to which we are subject is written in plain language, and offering training and education to those starting or defending a lawsuit. We need to promote resolving legal disputes through alternative processes that are more efficient, faster and less destructive than litigation. We need to greatly improve our funding of legal aid programs, especially with respect to the advancement and representation of women, Black people, Indigenous people, people of colour, members of the LGBTQ2+ communities and other marginalized groups. But, in the all too likely event that none of these fantasies materialize, we at least need to better fund our public legal education programs.