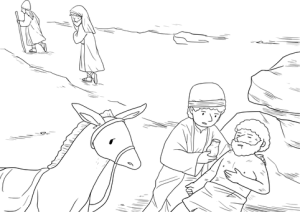

The New Testament story of the Good Samaritan is familiar to most people with even a basic knowledge of Christian teachings. Briefly, Jesus is reputed to have been asked “who is my neighbour?” In other words, give us an example of what would constitute an act of compassion for a stranger in trouble. So, Jesus told a story about a man who was mugged and left for dead at roadside. A priest passed by without lending a hand, then a Levite passed, ignoring the badly hurt man. Finally, a Samaritan (a member of a group who in Jesus’s time was ostracized by many) happened along, tended to the victim’s wounds and paid for his shelter while he was recuperating at a nearby inn.

The New Testament story of the Good Samaritan is familiar to most people with even a basic knowledge of Christian teachings. Briefly, Jesus is reputed to have been asked “who is my neighbour?” In other words, give us an example of what would constitute an act of compassion for a stranger in trouble. So, Jesus told a story about a man who was mugged and left for dead at roadside. A priest passed by without lending a hand, then a Levite passed, ignoring the badly hurt man. Finally, a Samaritan (a member of a group who in Jesus’s time was ostracized by many) happened along, tended to the victim’s wounds and paid for his shelter while he was recuperating at a nearby inn.

In modern legal terms, the question to be asked is not “who is my neighbour”? Instead, the legal question to be asked is do we owe a duty of care to give assistance to strangers in distress? For many of us, there’s a natural tendency to help somebody in distress, whether we come upon somebody who has collapsed on a sidewalk or we come upon a car accident.

..tort law professors and lawyers practising tort law may occasionally engage in debate about whether there should be a legally mandated, positive duty to render aid to strangers in distress.The question of whether there should be a legal duty to assist strangers in trouble has been the occasional source of debate among legal scholars over the years. However, generally throughout the parts of the world that have been influenced by or that have adopted the British common law tradition, so-called Good Samaritan Law has fallen short of legislating a positive legal duty to help strangers in distress. However, if people do render aid to strangers suffering a medical emergency or some sort of injury, there is some degree of protection in law. In Alberta, the actions of people who voluntarily help strangers in distress fall under the Emergency Medical Aid Act, R.S.A. 2000, c. E-7 (the Act).

The Act divides people who voluntarily help others in distress into four groups:

- physicians;

- registered health discipline members (e.g. licensed practical nurses, midwives or paramedics;

- registered nurses; and

- everyone else who is not a member of the first three groups.

According to section 2 of the Act, anyone, whether they are a member of the first three groups of health care professionals or simply a concerned person with no health care background, would not be held liable for any subsequent harm or death of a person in medical distress to whom voluntary assistance was given. However, there is an exception. If it could be proven that the subsequent harm or death resulted from the gross negligence of the person providing voluntary aid, then the Act will not absolve the person of liability.

In practical terms, the diligent nurse or other health care professional should always be cognizant that their greater knowledge and vaster skills set might mean their actions in a voluntary emergency aid situation would come under greater scrutiny.Unfortunately, the Act does not define what omission of action or action would constitute gross negligence. Nor does a search for “gross negligence” and “good Samaritan” of an online resource such as CanLII yield cases where the courts have had to adjudicate on emergency or crisis situations where strangers gave voluntary assistance to persons in medical distress.

That said, from numerous decisions arising in the context of contractual disputes and tort law cases generally, the following definitions of “gross negligence” have emerged:

- very great negligence;

- an obvious departure from the applicable standard of care;

- the doing of some act in such a careless fashion that wilfulness may be imputed to the negligence as opposed to simply not doing something; or

- an act or series of acts so egregious that a total lack of care for the consequences can be imputed.

A plain reading of the Act would suggest that everyone, regardless of whether they be a registered nurse, other health care professional, or layperson would be held to the same standard of care. In practical terms, the diligent nurse or other health care professional should always be cognizant that their greater knowledge and vaster skills set might mean their actions in a voluntary emergency aid situation would come under greater scrutiny.

For example, registered nurses in Alberta have a professional duty in accordance with section 1 (Professional Responsibility) of the College and Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta (CARNA) Nursing Practice Standards to be accountable at all times for their actions and to conduct themselves in accordance with all current legislation relevant to their profession. Such knowledge includes awareness of legislation ancillary to their profession, which would arguably include the Emergency Medical Act, or the “Good Samaritan Law” as it is more colloquially known.

However, if people do render aid to strangers suffering a medical emergency or some sort of injury, there is some degree of protection in law. In conclusion, tort law professors and lawyers practising tort law may occasionally engage in debate about whether there should be a legally mandated, positive duty to render aid to strangers in distress. Those same law professors and lawyers may also engage in conjecture about whether despite what the “Good Samaritan Law” says, registered nurses (and other health care professionals) could or should in fact be held to a higher standard in rendering emergency aid when they are on their own time away from the job. The safe and practical recommendation would be that when a nurse or other health care professional happens upon the scene of an emergency or crisis where somebody is in medical distress, they should act as their professional codes require them to do, but also act with all the diligence that is demanded of them by their respective professions.

Please note this article provides general information only so does not constitute legal advice.