Fifty years ago, the concept of a human right to a healthy environment was viewed as a novel, even radical, idea. Today it is widely recognized in international law and endorsed by an overwhelming proportion of countries. Even more importantly, despite their recent vintage, environmental rights enjoy constitutional protection in over 100 countries. These provisions are having a remarkable impact, including stronger environmental laws, better enforcement of those laws, landmark court decisions, the cleanup of pollution hotspots, and the provision of safe drinking water.

Fifty years ago, the concept of a human right to a healthy environment was viewed as a novel, even radical, idea. Today it is widely recognized in international law and endorsed by an overwhelming proportion of countries. Even more importantly, despite their recent vintage, environmental rights enjoy constitutional protection in over 100 countries. These provisions are having a remarkable impact, including stronger environmental laws, better enforcement of those laws, landmark court decisions, the cleanup of pollution hotspots, and the provision of safe drinking water.

Canada, unfortunately, is a holdout. Our Constitution does not mention the environment, and Canada is one of a dwindling number of countries that refuse to recognize the right to a healthy environment. There are six compelling reasons why Canada needs to modernize its Constitution to include this fundamental human right.

First, Canada trails behind other countries when it comes to protecting the environment. According to the Conference Board of Canada, we rank 15th out of 17 large, wealthy, industrialized countries on a comprehensive index of environmental performance indicators. A study done by Simon Fraser University researchers ranked Canada’s environmental record 24th out of 25 nations in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Our magnificent natural heritage is at risk.

Second, our poor environmental record inflicts a high cost on human health and well-being. The World Health Organization estimates that 30,000 premature deaths in Canada each year are caused in whole or in part by environmental hazards. This eye-opening figure is consistent with research done by the Canadian Medical Association estimating that air pollution alone causes tens of thousands of premature deaths (and billions of dollars in preventable health care costs) annually.

Third, the Constitution’s silence on environmental protection has been acknowledged as problematic for more than 100 years. Back in 1912, Prime Minister Laurier’s Commission on Conservation reported that constitutional uncertainty about environmental protection was undermining efforts to address water pollution. In 1997, the Supreme Court of Canada came within a whisker of striking down critical provisions of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act because of the absence of a clear constitutional basis for the law.

Fourth, environmental rights and responsibilities have been a cornerstone of indigenous legal systems for millennia. For the Haida, the Anishinabek, and the Mi’kmaq, the Earth’s sentience creates corresponding rights and obligations for both humans and Nature. As the Supreme Court of Canada has repeatedly observed, incorporating indigenous law into the Canadian legal system is an important step toward reconciliation with Aboriginal people.

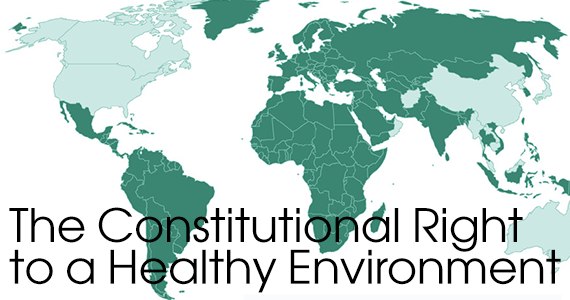

Fifth, as of 2012, 177 of the world’s 193 UN member nations recognize this right, either through their constitutions, environmental legislation, court decisions, or ratification of an international agreement (see Map 1). The only remaining holdouts are the U.S., Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, China, Oman, Afghanistan, Kuwait, Brunei Darussalam, Lebanon, Laos, Myanmar, North Korea, Malaysia, and Cambodia. The rapid spread of this right is remarkable, given that its first formal articulation came just 40 years ago in the Stockholm Declaration that emerged from the first global earth summit. Today, citizens in 108 nations – from Argentina to Zambia – enjoy a constitutionally protected right to a healthy environment. In more than 100 countries, the right is explicitly recognized in environmental legislation. As well, 120 countries – in Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa – have signed legally binding human rights treaties that include the right to a healthy environment.

Sixth, an overwhelming majority of Canadians – over ninety percent – believe that governments should recognize their right to a healthy environment. Indeed, a majority of Canadians erroneously believe that the right to a healthy environment is already included in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Would constitutional recognition of environmental rights and responsibilities make a difference in Canada? Based on our own experience with advances in respect for human rights since repatriation of the Constitution in 1982, and the experiences of other nations where the right to a healthy environment enjoys constitutional status, the answer is definitely yes. There has been tremendous progress in protecting certain human rights in Canada since 1982, as demonstrated by the sea change in respect for Aboriginal rights and the affirmation – both legal and, more importantly, cultural – of same-sex marriage.

New evidence from across the globe demonstrates that constitutional environmental rights and responsibilities are a catalyst for stronger environmental laws, better enforcement of those laws, and enhanced public participation in environmental governance. Most importantly, there is a strong positive correlation between superior environmental performance and constitutional provisions requiring environmental protection. For example, nations with green constitutions have smaller ecological footprints and have reduced some types of air pollution up to ten times faster than nations without environmental provisions in their constitutions. Ultimately this means people are breathing cleaner air, drinking safer water, and living in healthier environments.

For example, citizens living in what was once one of the most polluted watersheds in Argentina used their constitutional right to a healthy environment to compel federal, provincial, and municipal governments to undertake

an unprecedented cleanup and restoration effort. Collectively, these governments are spending more than $1 billion annually over a period of ten years to upgrade drinking water and sewage treatment infrastructure, improve environmental monitoring and enforcement, and restore the health of both residents and the Riachuelo River. By comparison, Canada’s efforts to clean up pollution and contaminated areas around the Great Lakes are slow and grossly inadequate, creating ongoing environmental hazards for people living in that region.

Although Canada’s Constitution is silent on environmental protection, the right to a healthy environment is recognized in five provinces and territories. Quebec put the right into its Environmental Quality Act in 1978 and added it to its provincial Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms in 2006. Ontario enacted a comprehensive Environmental Bill of Rights in 1993. The Yukon, NWT, and Nunavut have modest environmental rights legislation. In 2011, with the unanimous support of the opposition parties, Parliament came very close to passing Bill C-469, the Canadian Environmental Bill of Rights.

While these laws are better than nothing, they are far weaker legally, politically, and symbolically than constitutional recognition of the right to a healthy environment. The Constitution is our highest and strongest law, as all laws, regulations, and policies must be consistent with it. On a deeper level, constitutions reflect the most deeply held and cherished values of a society. As a judge once stated, “a Constitution is a mirror of a nation’s soul.”

There are three ways that the right to a healthy environment could gain constitutional recognition in Canada:

- direct amendment of the Constitution, requiring Parliament’s approval and the support of seven of the ten provinces, secured within a three year period;

- litigation resulting in a court decision that there is an implicit right to a healthy environment in s. 7 of the Charter (the right to life, liberty, and security of the person); and

- a judicial reference resulting in a court decision that there is an implicit right to a healthy environment in s. 7 of the Charter.

Constitutional change is always difficult in Canada, though not impossible. There have been 11 amendments since 1982 including two revisions of the Charter. However, given the position of the current majority government, an environmental amendment is unlikely in the short term.

There is a case before the courts in Ontario in which Ada Lockridge and Ron Plain, members of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation, are arguing that the Ontario government’s decision to allow additional pollution from a Suncor refinery near their community violates their rights to “life, liberty, and security of the person” and equality under the Charter. In essence, their argument is that the Charter contains an implicit right to a healthy environment. Although they face an uphill battle, their case is buttressed by the fact that courts in at least twenty other nations have concluded that the right to life includes an implicit right to a healthy environment.

The judicial reference is a uniquely Canadian legal process through which the federal, provincial, and territorial governments have the power to ask courts to answer important legal questions. The process has been used over a hundred times to address controversial issues including the ownership of offshore natural resources, the legality of Quebec secession, and same-sex marriage. The most famous judicial reference is the Persons’ Case, brought in the late 1920s in response to a compelling public campaign led by Nellie McClung. The federal government asked the Supreme Court of Canada to determine whether women were persons for purposes of being eligible for appointment to the Senate. The Court, infamously, said no. Fortunately, at that time Supreme Court decisions could be appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the U.K. Common sense prevailed, women were recognized as persons, and the case marked a watershed moment in the battle for women’s rights in Canada. A Canadian government could ask the courts whether the right to a healthy environment is implicit in the right to life. An affirmative answer would result in constitutional recognition of this fundamental human right, consistent with the stated values of the people of Canada.

In light of the remarkable international developments, widespread public support, and compelling reasons for Canada to move in this direction, now is the time to lay the groundwork for constitutional recognition of environmental rights and responsibilities. This may include enacting environmental bills of rights at the federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal levels as stepping-stones towards the ultimate goal of constitutional reform.

Enshrining environmental rights and responsibilities in the Constitution is not a magic wand that would instantly solve Canada’s complex ecological challenges. However, doing so would force Canadians to make sustainability a genuine priority, resulting in changes that would make Canada a greener, cleaner, wealthier, healthier, happier nation in the long run.

For additional information, please see

David R. Boyd, The Right to a Healthy Environment: Revitalizing Canada’s Constitution (UBC Press, 2012)

David R. Boyd, The Environmental Rights Revolution: A Global Study of Constitutions, Human Rights, and the Environment (UBC Press, 2012)