Parenting coordination is a form of alternative dispute resolution (“ADR”) targeting the needs of separated parents who are experiencing entrenched conflict and are having difficulty implementing court orders and parenting plans. Through different techniques such as negotiation, problem-solving, education, mediation, and – in some jurisdictions – decision enforcement, the goal of the parenting coordinator (“PC”) is to help lower conflict between the parents and keep their dispute outside of the courtroom. This ADR is gaining more and more popularity in North America and although research on its efficacy is still scarce, the literature is so far showing promising results.

Parenting coordination is a form of alternative dispute resolution (“ADR”) targeting the needs of separated parents who are experiencing entrenched conflict and are having difficulty implementing court orders and parenting plans. Through different techniques such as negotiation, problem-solving, education, mediation, and – in some jurisdictions – decision enforcement, the goal of the parenting coordinator (“PC”) is to help lower conflict between the parents and keep their dispute outside of the courtroom. This ADR is gaining more and more popularity in North America and although research on its efficacy is still scarce, the literature is so far showing promising results.

The body of literature on the voice of the child in post-separation interventions has led to the conclusion that children want to have the opportunity to be heard in matters that concern them. Children do not want to make choices regarding custody arrangements but they do want their input to weigh in on the decisional scale. Moreover, research shows that children are more likely to consider custody arrangements to be fair if they are given a say in the decision-making process. Not only do most children want to be heard in post-separation proceedings, it is one of their fundamental rights as part of the United Nations Convention for the Rights of the Child, ratified by Canada (Article 12):

Paragraph 1: “States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.”

Paragraph 2: “For this purpose, the child shall in particular be provided the opportunity to be heard in any judicial and administrative proceedings affecting the child, either directly, or through a representative or an appropriate body, in a manner consistent with the procedural rules of national law.”

The two children who were against child inclusion also shared an overall negative view of their experience in parenting coordination.Parenting coordination is an intervention for parents in which children may occasionally be asked to participate. There is, however, no consensus as to if and how children should be given a voice in parenting coordination. In the Parenting Coordination Guidelines published by the Association of Family and Conciliation Courts (“AFCC”) in 2005, the directions about child inclusion are vague and the decision to include them is left to the PC in charge. To our knowledge, no study so far has focused on the inclusion of children in parenting coordination. Joan Kelly, a pioneering PC in California, has emphasized the importance of meeting children as part of the parenting coordination process, noting many benefits of this practice – including empowerment of the child and increased efficacy of the intervention. However, she and others also warn that PCs should have sufficient training and experience with interviewing children. Furthermore, she adds that children should only meet the PC when the content of the parental dispute concerns them and is suitable in light of their age and developmental capabilities.

Inclusion of children – What we learned from the Montreal parenting coordination pilot project

As part of a pilot project that took place between 2012 and 2014, 10 high conflict families living in the Montreal area received free parenting coordination services. The intervention was provided by two PCs hired by the Ministry of Justice. Children from eight of the 10 families met at least once with the PC during the intervention process. Following the conclusion of parenting coordination services, ten of these children (aged between 8 and 17 years-old) were asked to participate in a research project in order to better understand their experience. These children met with the PC three times on average during the pilot project, sometimes alone, or sometimes in the presence of their sibling(s). Parents and PCs were also surveyed as to their opinion on the inclusion of children in parenting coordination as part of this research.

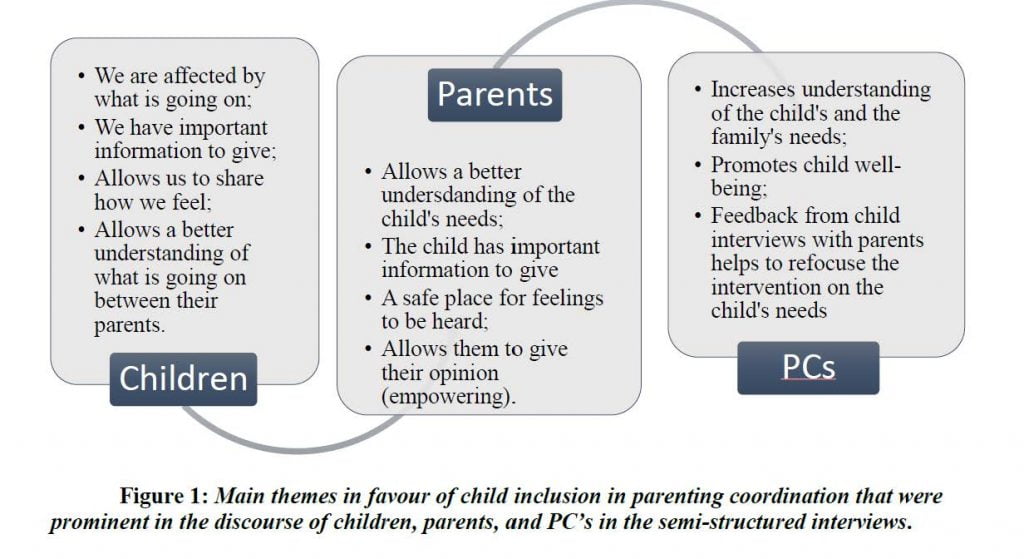

Qualitative analysis of the data collected through the semi-structured interviews conducted with the children, parents, and PCs shows that all categories of participants agree on the importance on giving children a voice in parenting coordination. More specifically, 8 out of the ten children interviewed (80%), 12 out the 14 parents (86%) and both PCs explicitly expressed being in favour of child inclusion in parenting coordination. The main reasons mentioned by participants are shown in Figure 1:

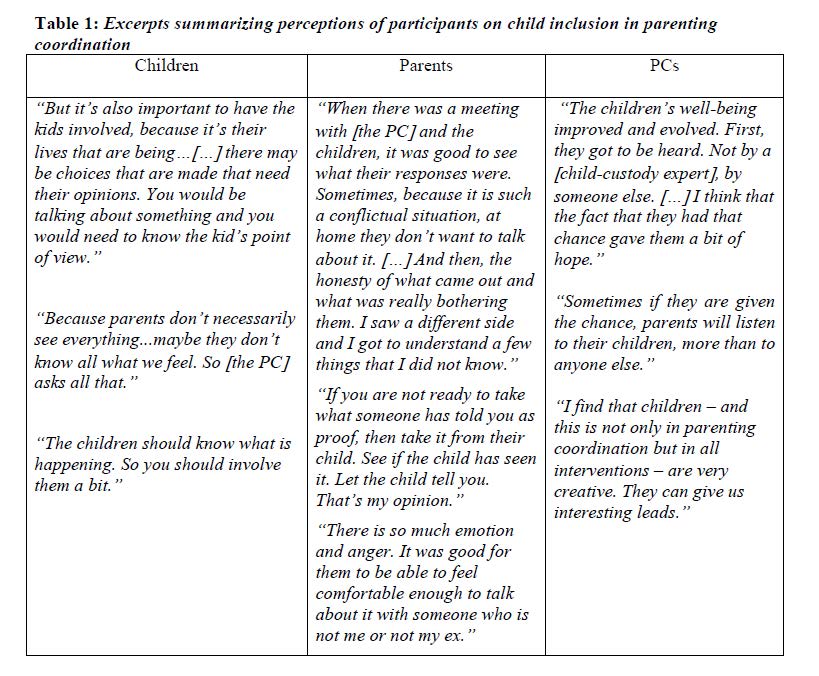

The excerpts in Table 1 summarize the perceptions of most of the children, parents, PCs interviewed:

Furthermore, four out of the 10 children interviewed expressed they would have liked to meet with the PC more often and felt they were not given enough of a say. The children’s discourse also highlights the importance of respecting the children’s wishes to be met alone and/or with their siblings.

“I would have liked to see him alone as well, because with [my siblings] well… they didn’t necessarily have the same opinion as me.”

“[The PC should meet] [a]ll of them together. They will feel more comfortable all together. [If you meet the PC alone] you think it is more serious. When you are with people you know, you are more comfortable and you feel like expressing yourself more.”

Joan Kelly, a pioneering PC in California, has emphasized the importance of meeting children as part of the parenting coordination process, noting many benefits of this practice – including empowerment of the child and increased efficacy of the intervention. The two children who were against child inclusion also shared an overall negative view of their experience in parenting coordination. These children were estranged from a parent prior to the pilot project, which may have made their participation in parenting coordination more painful. A more detailed reflection on these cases is available in the full article published in the Journal of Divorce and Remarriage.

Parents’ discourse was very much in favor of child inclusion. Most expressed they would have liked their child(ren) to meet more often with the PC during the process. Although two parents expressed some reluctance about child inclusion, mainly because they felt the conflict didn’t concern them or that they had seen enough professionals about the divorce, both those parents agreed for their children to meet with the PC and were able to see some benefit to it.

Interviews with both PCs involved in the pilot project proved very insightful as to this relatively unknown practice. In all instances where the children met with a PC (eight families), the PC saw the meeting as positive and useful. Both shared that these meetings enhanced their understanding of the family dynamics and helped clarify the children’s needs. Furthermore, hearing from the child directly allowed the PCs to assess the level of conflict of loyalty to parents. It also allowed the PCs to detect, in some cases, if a child’s discourse was aligned with one of the parents. While sharing enthusiasm for child participation, both PCs also acknowledge that it is a practice that warrants caution and proper training. For instance, confidentiality and its limits need to be discussed with the child from the outset. Furthermore, PCs have to choose carefully which information they will share with parents and how they will share it in a way that will protect the child’s relationships. PCs also need to be careful not to conduct meetings in a way that would make the child feel that they have to take a side between their parents. The PCs should clarify their role and the goal of these meeting with the child, and explain how they will use what is being discussed during these meetings. This is why specific training and relevant experience in interviewing children in post-separation interventions is needed.

The body of literature on the voice of the child in post-separation interventions has led to the conclusion that children want to have the opportunity to be heard in matters that concern them. But is child-inclusion in parental coordination a must? It seems that in cases where there is a severe degree of parental alienation, meeting with the child might negatively feed the conflict and the child’s alignment to the parents. In these instances, the PC might want to refrain from encouraging the child to complain about one parent and to believe that venting these feelings is serving their best interest. More intensive and individualized services for these children and their family might also be necessary in those situations. However, in most cases, child inclusion brought many benefits, not only for the child but also for the intervention itself. Moreover, most children want the opportunity to be heard. Therefore, the results from this pilot show that in most cases, children should be given a voice in parenting coordination. The PC can contribute to children’s well-being and adaptability by making decisions with proper training, judgment, and sensitivity to the child’s hopes and needs that, after all, will affect their daily lives.