Beechwood Cemetery Foundation: Great Canadian Profile Plaque

This chronology was compiled to convey, by historic milestones, how the Indian Residential School system came to be, how it embodied attitudes of its time, how critics were dismissed, and how finally the deep harm it did to many members of generations of Indian children was exposed in the course of a reconciliation process that continues. While Canada is doing its best to compensate, in many senses, for the failings of the system, much of the damage to individuals, and to First Nations culture, can never be put right.

1755 – Indian Department created as branch of British military to establish and maintain relations with Indians.

1820 – This decade sees Anglican and Methodist missionary schools established in Upper Canada and Red River settlement.

1842 – Governor General Sir Charles Bagot appoints Commission to report on “the Affairs of the Indians in Canada.”

1844 – Bagot Commission finds reserve communities in a “half-civilized state”; recommends assimilationist policy, including establishment of boarding schools distant from child’s community, to provide training in manual labour and agriculture; portends major shift away from Royal Proclamation of 1763 policy that Indians were autonomous entities under Crown protection.

1847 – Dr. Adolphus Egerton Ryerson, Methodist minister and educational reformer, commissioned by Assistant Superintendent General of Indian Affairs to study Native education, supports Bagot approach (as does Governor General Lord Elgin); proposes model on which Indian Residential School system was built.

1856 – “Any hope of raising the Indians … to the … level of their white neighbours, is yet a … distant spark”: Governor General Sir Edmund Head’s Commission “to Investigate Indian Affairs in Canada.”

1857 – Gradual Civilization Act passed; males “sufficiently advanced in the elementary branches of education” could be enfranchised (they would no longer be “Indians,” and could vote).

1861 – St. Mary’s Mission Indian Residential School, Mission, and Presbyterian Coqualeetza Indian Residential School, Chilliwack, first residential schools in B.C., established.

1862 – Blue Quills Indian Residential School (Hospice of St. Joseph / Lac la Biche Boarding School) established at St. Paul, AB; first residential school on the Prairies.

1867 – Confederation: British North America Act (now Constitution Act, 1867) establishes federal jurisdiction over Indians. Thus, while education is under provincial jurisdiction, Indian matters including education are federal.

Fort Providence and Fort Resolution Indian Residential Schools established; first residential schools north of 60⁰.

1871 – Treaty No. 1 entered into at Lower Fort Garry: “Her Majesty agrees to maintain a school on each reserve … whenever the Indians of the reserve should desire it.” This promise, repeated in subsequent treaties (though hedged in Treaties No. 5 on), reflected desire of Indian leadership to ensure transition of their youth to demands of anticipated newcomer society.

1876 – Indian Act passed into law by Parliament.

1879 – Nicholas Flood Davin, journalist and defeated Tory candidate, commissioned by Prime Minister Macdonald, also Minister of the Interior, to produce proposal for Indian education; visits US industrial schools grounded in policy of “aggressive civilization”; produces Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds. Four residential schools already operated in Ontario; “mission schools” planned for the west. This date generally taken to mark beginning of Indian Residential Schools, though the system had early predecessors in New France and New Brunswick, and several schools were already operating.

Duncan Campbell Scott, best known later as a “Confederation poet,” joins Indian Affairs at age 17 as “copying clerk,” at direction of Macdonald.

1883 – First industrial school established, at Battleford, modelled on Davin Report.

1885 – Residential schools necessary to remove children from influence of the home only way “of advancing the Indian in civilization”: Lawrence Vankoughnet, Deputy Superintendent General, to Prime Minister Macdonald. Despite treaty promises, reserves lacked schools; removal, often forcible, of pupils to residential schools is option chosen by government.

1890 – Physician Dr. G. Orton reports to Indian Affairs that tuberculosis in the schools could be reduced by half; measures rejected as “too costly.”

1892 – Regulations passed giving control over daily school administration to churches: Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist. (In 1925, Methodists joined most Presbyterians and others to form United Church, which continued to run schools.)

1896 – Programme of Studies issued; stresses importance of replacing “native tongue” with English. Children forbidden to speak their native language, even to each other, and punished for doing so. This continued to be the policy for life of the system.

1904 – Dr. Peter Bryce appointed “Medical Inspector” to the Departments of the Interior and Indian Affairs.

1904 – Minister Sir Clifford Sifton announces closure of industrial schools – large urban institutions – in favour of boarding schools. They are closed over the next two decades.

1907 – Dr. Bryce visits 35 schools; reports appallingly unsanitary conditions, micro-organism-bearing ventilation, high death rates; “the almost invariable cause” is tuberculosis.

“The appalling number of deaths among the younger children … brings the Department within unpleasant nearness to the charge of manslaughter”: Hon. S.H. Blake, K.C., Chair of Advisory Board on Indian Education (partner in what is now national law firm Blake, Cassels & Graydon), to Minister Frank Oliver.

1908 – Indian Affairs Accountant F.H. Paget reports school buildings in bad condition.

1909 – Duncan Campbell Scott appointed Superintendent of Indian Education.

1910 – The children “catch the disease … in a building … burdened with Tuberculosis Bacilli”: Duck Lake Indian Agent MacArthur on the continuing prevalence of tuberculosis.

1912 – “… in the early days of school administration … [t]he well-known predisposition of Indians to tuberculosis resulted in a very large percentage of deaths among the pupils … fifty percent of the children who passed through these schools did not live to benefit from the education which they had received therein”: Scott, in an essay in the authoritative 22-volume Canada and its Provinces.

1913 –Scott appointed Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs (deputy minister), reporting to Minister of the Interior and Superintendent General Dr. William A. Roche.

1919 – Position of Medical Inspector for Indian Agencies and Residential Schools abolished (in the year of the Spanish ‘flu) by order in council on recommendation of Scott “for reasons of economy.”

1920 – “I want to get rid of the Indian problem”: D.C. Scott to Parliamentary Committee. A Scott-instigated amendment to the Indian Act, with church concurrence, compelled school attendance of all children aged seven to fifteen. Though no particular kind of school was stipulated, Scott favoured residential schooling to eliminate the influences of home and reserve and hasten assimilation.

“I am afraid I cannot give a very encouraging answer to the question. We are not convinced that it is increasing, but it is not decreasing”: Prime Minister Arthur Meighen, former Minister of the Interior, on being asked whether tuberculosis was increasing or decreasing amongst the Indians.

1922 – Dr. Bryce publishes The Story of a National Crime: Being an Appeal for Justice to the Indians of Canada, the Wards of the Nation, Our Allies in the Revolutionary War, Our Brothers-in-Arms in the Great War. He charges that, for 1894-1908, within five years of entry 30% to 60% of students had died, an avoidable mortality rate had healthy children not been exposed to children with tuberculosis: A “trail of disease and death has gone on almost unchecked by any serious efforts on the part of the Department of Indian Affairs.” His 1907 recommendations on tuberculosis control not given effect, he says, “owing to the active opposition of Mr. D.C. Scott.”

1923 – “Residential Schools” adopted as official term, replacing “boarding” (55) and “industrial” (16), housing 5,347 children.

1932 – Scott retires as Deputy Superintendent General after more than 52 years in the department. The anthologist John Garvin writes that Scott’s “policy of assimilating the Indians had been so much in keeping with the thinking of the time that he was widely praised for his capable administration.” He embodied a fundamental contradiction: While a rigid and often heartless bureaucrat, “his sensibilities as a poet [were] saddened by the waning of an ancient culture” (Canadian Encyclopedia).

1939 – 9,027 children are in 79 residential schools run by Catholic (60%), Anglican (25%), United and Presbyterian churches. “1939 [was] the approximate mid-point of the history of the system”: John S. Milloy, A National Crime.

1944 – Consensus develops among senior Indian Affairs officials that integration into provincial systems should replace segregated Aboriginal education.

1951 – Indian Act of 1876, with many amendments, repealed; replaced with modernized Indian Act (today’s Act, with amendments) conceptually similar to previous Act.

1955 – Jean Lesage, Minister of Northern Affairs and National Resources, department responsible for Inuit (then known as Eskimos), gets Cabinet approval for broad education policy in North. General policy is to substitute settlements for nomadic life. A school is built at Chesterfield Inlet, followed by Coppermine, and ten “hostels.” Some Inuit had formerly been sent south to Indian Affairs schools. “Destitute” Métis were sometimes also enrolled.

1969 – Indian Affairs takes over sole management of residential schools from churches.

1969 – Indian Affairs Minister Jean Chretien produces assimilationist “White Paper” to abolish Indian status; strongly opposed by Indian organizations. Alberta Indian Association produces Citizens Plus, known as “Red Paper,” in response. White Paper retracted two years later.

1971 – Blue Quills School, St. Paul, AB, becomes first Indian-run school, following month-long contentious occupation by elders and others.

1972 – National Indian Brotherhood (predecessor of Assembly of First Nations) produces Indian Control of Indian Education, advocating greater band control of education on reserves; adopted next year by government.

1975 – Six residential schools close this year; 15 remain.

1976 – NIB proposes amendments to Indian Act to provide legal basis for Indian control of education; rejected by government.

1978 – National Film Board produces first film ever on residential schools: Wandering Spirit Survival School, about a non-traditional school organized by parents who had themselves survived residential schools.

1984 – 187 bands are operating own (day) schools, half in B.C.; rest mainly on Prairies.

1993 – Archbishop Michael Peers, Primate of Anglican Church of Canada, apologizes to survivors of Indian residential schools on behalf of the Church.

1996 – Gordon Indian Residential School, Punnichy, Saskatchewan, closes; last of 139 Indian Residential Schools in Canada.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples recommends public investigation into violence and abuses at residential schools. Report brings these issues to national attention.

1998 – Government responds to RCAP Report with Statement of Reconciliation, including apology to those sexually or physically abused while attending residential schools, and establishment of Aboriginal Healing Foundation to assist Aboriginal communities to build healing processes that address legacy of system, with $350 million endowment.

2001 – Federal Office of Indian Residential Schools Resolution Canada created to manage and resolve large number of abuse claims filed by former students, resulting in 17 court judgments.

2003 – National Resolution Framework launched, including Alternative Dispute Resolution process, an out of court process providing compensation and psychological support for former students who were physically or sexually abused or had been wrongfully confined.

2004 – Assembly of First Nations (AFN) Report on Canada’s Dispute Resolution Plan to Compensate for Abuses in Indian Residential Schools leads to resolution discussions.

RCMP Commissioner Giuliano Zaccardelli expresses sorrow for the force’s role in the residential school system.

2005 – $1.9 billion compensation package announced to benefit former residential school students.

2007 – Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, largest class action settlement in Canadian history, negotiated and approved by parties, and Courts in nine jurisdictions, implemented. Of the 139 schools ultimately included in the settlement, 64 were Roman Catholic, 35 Anglican, 14 United Church, and the balance other or no denomination. The objective was reconciliation with the estimated 80,000 former students then still living, of over 150,000 enrolled since 1879. Elements are,

- Common Experience Payment to be paid to all eligible former students who resided at a recognized Indian Residential School;

- Independent Assessment Process for claims of sexual or serious physical abuse;

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission;

- Commemoration Activities;

- Measures to support healing such as the Indian Residential Schools Resolution Health Support Program and an endowment to the Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

Survivors report harsh and cruel punishments, suicides of others, physical, psychological and sexual abuse, poor quality and meagre rations and shabby clothing in the schools, and inability on leaving to belong in either the Aboriginal or larger world. Posttraumatic stress disorder, major depression, anxiety disorder and borderline personality disorder have been diagnosed, and many have criminal records.

2008 – Prime Minister Harper offers formal apology in Parliament for the Indian Residential Schools, in presence of Aboriginal delegates and church leaders. Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission established June 1, with five-year mandate, later extended to 2015.

2009 – AFN Chief Phil Fontaine meets Pope Benedict XVI at Vatican. Pope Benedict expresses “sorrow” and “sympathy and prayerful solidarity,” but avoids apologizing.

After a rocky start, with resignations of original Commissioners, Truth and Reconciliation Commission begins work under Justice Murray Sinclair, an Aboriginal Manitoba judge who became the province’s Associate Chief Justice in 1988.

2010 – Truth and Reconciliation Commission begins hearings in Winnipeg.

2011 – University of Manitoba president David Barnard apologizes to Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada for institution’s role in educating people who operated the residential school system.

2012 – Truth and Reconciliation Commission releases Interim Report; reviews progress, explains statement gathering and document collection process. Tells of degrading treatment, unwarranted punishments, and physical and sexual abuse by “loveless institutions.” Makes numerous recommendations respecting public education about residential schools and about mental health and wellness programs, especially in the North, and that Canada and churches establish a cultural revival fund. Notes mandate to establish a National Research Centre.

Interim Report can be accessed at: http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/TRC/Interim%20report%20English%20electronic.pdf.

Over 105,000 applications for Common Experience Payments were received by Canada by 2012 deadline; over 79,000 were found eligible and paid, the average amount being $19, 412. September 19 was final deadline for Independent Assessment Process claims.

2014 – Commission’s hearings in more than 300 communities wrap up. “National Events,” in Winnipeg, Inuvik, Halifax, Saskatoon, Montreal and Vancouver have been held, as required by the Settlement Agreement, the final one taking place March 27-30 in Edmonton.

2015 – Final year for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission; related events occur:

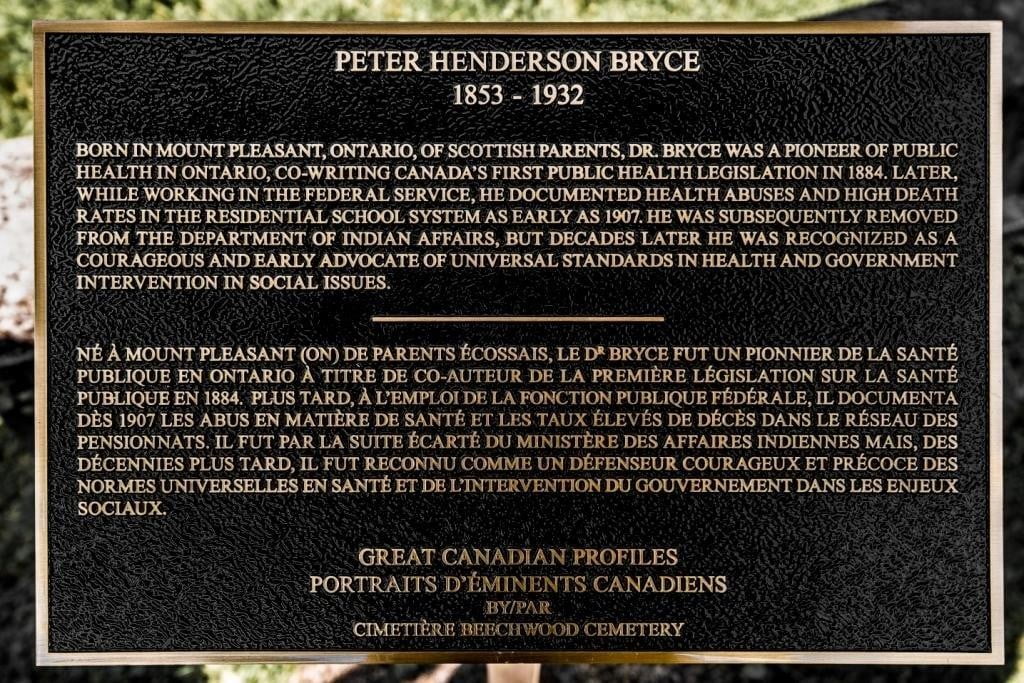

- August 16: Dr. Peter Bryce (1853-1932), author of The Story of a National Crime, is honoured by the unveiling of a plaque in his honour at Ottawa’s Beechwood Cemetery, the National Cemetery of Canada.

- November 1: The plaque at Beechwood Cemetery honouring Scott as a poet is modified to include mention of his role in residential schools.

- December 15: The final six-volume, 3,231-page TRC report is released. The TRC also produced a summary and five other companion volumes, 2012-15. The summary can be accessed at http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf.

- December 18: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission closes its doors. As required by the Settlement Agreement, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation opens, with a mandate to hold and make accessible all of the materials gathered by the Commission throughout its mandate. It is located at 177 Dysart Road on the University of Manitoba Fort Garry Campus in south Winnipeg: nctr.ca.