Namibia is located on the west side and in sub-Saharan Africa. It is the fourth largest country in Africa but, as of 2011, had a scant population of around 2.3 million inhabitants. It is a country of stark contrasts, perhaps largely due to the fact that Namibia is arid and has limited capacity to sustain much life. From 1884 until 1915 it was a German colony, and thereafter, was first administrated under a C-Mandate of the League of Nations, and later, annexed by South Africa. Namibia attained independence on March 21, 1990, and now has a constituted representative democracy endowed with an independent judiciary and strongly entrenched human rights and freedoms. Like many former colonies, prior to the apartheid administration period, Namibia suffered from the plights of oppression and repressive criminal justice measures. Therefore, it offers a unique opportunity to look at an emerging/evolving justice system. In 2012, while on institutional leave, I had the pleasure to be able to visit, teach, and observe various aspects of Namibia’s criminal justice system. However, due to limited space, I will confine my observations in this article to their juvenile justice system. First, however, here is a brief overview of crime and justice in the country.

According to a number of accounts, Namibia is a comparatively peaceful country but the level of fear and/or apprehension towards personal safety is evident when one visits Windhoek, the capital. Virtually every house is walled and topped with an electrified fence or barbed wire, and virtually every business has security staff (many from the G4S company). The police appear to be under-resourced and only modestly trained to be able to conduct investigations of more serious crimes. One local scholar described the police cells as “hell on earth” and juveniles are often kept together with adult offenders. The court system is marred by delays as magistrates and judges carry an extremely high case load. Finally, corrections, although having come a long way since independence, is still fraught with old technology, considerable pre-independence physical infra-structure, and is poorly resourced. It must deal with issues of overcrowding, HIV, and a general lack of means to effectively deal with inmates. However, not all is gloom, because across the system there is clear evidence that, legislatively, the criminal justice system is taking steps to ensure that the provisions for advancing and improving the administration of justice are in place. What is lacking, however, is the human, resource, and financial capacity to match its stated objectives with its practices. For example, while statistics are gathered by each of the criminal justice components, there is no national crime statistics gathering mechanism in place.

I choose to focus on juvenile justice since as we euphemistically say: “the youth of today are the leaders of tomorrow”, and unlike adults, they have no voice in how legislation pertaining to their criminal behaviour is scripted. How the State responds to the plight of its youth is revealing.

A nation of firsts

“No tree can live without roots and no man without his kin” – Namibian saying

Namibia became the first country in Africa to ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in September 1990. In being a signatory of the UN Convention (i.e., an international human rights agreement), Namibia expressed its intention to not only create greater awareness of children’s human rights, but also to implement legislation to entrench fundamental human rights for young persons. A survey shortly after ratifying the Convention revealed that a majority of juvenile offenders had been incarcerated without access to any form of legal counsel. In addition, a majority had been detained in excess of three months during their pre-trial detention period.

In 1994, Namibia became one of the first African countries to establish a Juvenile Justice Forum (JJF) which, during its lifespan, facilitated a range of positive reforms for juvenile offenders.

Unfortunately, mainly due to the withdrawal of foreign funds by Austria in 2006, the program and initiative could not be sustained and it slipped into an abyss.

Namibia also became the first African country to provide a comprehensive written report on how well Namibia was complying with its obligations to the CRC. At the time, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child noted, in particular, its concerns as to the conformity of Namibian practices in dealing with child offenders with the CRC, in particular with respect to Articles 37 and 40, as well as other relevant international instruments such as the Beijing Rules and Riyadh Guidelines.

As a continent, Africa recognized that it shared unique social and cultural characteristics that distinguished it from the rest of the world, so it created the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. Namibia became one of the first countries to ratify the Charter, and in doing so, expressed its commitment to adopting legislation and reform that would honour the Charter. The three primary characteristics of the Charter are:

- protection of young persons;

- provision of legal service; and

- participation in legal processes.

Finally, Namibia became one of the first few African countries to sign the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict in September 2000. And in 2003, Namibia drafted its Child Justice Bill. Among other things, the proposed Bill would govern cases in which children (under the age of 21) are charged with crimes and reflect elements of Ubuntu (a type of communal approach to justice) when dealing with young offenders.

Collectively, it can be said that, in principle, since gaining independence, Namibia has formally expressed a strong commitment to ensure the human and legal rights of its young offenders. However, as Dr. Stefan Schulz, a faculty member in the Department of Criminal Justice and Legal Studies at the Polytechnic of Namibia noted nearly a decade ago, there is still no national legislation to address the needs of young persons who come into conflict with the law. Any such provisions fall under a range of other criminal justice legislation. Hence, while on a paper of promise (i.e., Child Justice Bill) the country embraces what I have described elsewhere as a ‘welfare model’, in practice and according to the currently relevant legislation, juvenile justice in Namibia is more representative of a ‘justice model’ – concerned more with retribution than with resocialization, reintegration, and/or treatment.

A system in (dis)repair

The draft Child Justice Bill stated that children between the ages of 7-14 are not capable of committing a crime because they “do not have the capacity distinguish between right and wrong”. Now renamed the Child Care and Protection Bill, the revised Draft Bill clearly is descriptive of a welfare model, but it has yet to replace the Children’s Act 33 from 1960! Under the existing Act parents still have the “right to punish and exercise discipline” of their children. However, under the proposed new Bill, the focus will shift to a parent’s obligation to respect a child’s physical integrity. Whether the non-specific section of the new Bill will shift to excluding corporal punishment as a disciplinary option may be suspect. A recent national survey found that over 60 per cent of parents admitted to using corporal punishment (i.e., smacking or caning) their children and that it was generally seen to be acceptable especially for the father in the household. And, while the Namibian government also wants to consult with South Africa, which introduced new legislation for juveniles, in order to ensure that it doesn’t experience its mistakes, the government has yet to do so.

Unfortunately, while the Bill continues to languish in Parliament, there are other indications that the country is trying to ensure the well-being and welfare of its youth. For example, school attendance and the national literacy rate are higher than in most other African nations, polio among children and youth has all but been eliminated since 1990 and the incident rate of HIV transmission has been steadily declining among children and young people. Similarly, the inclusion of a clause on the rights of the child in the Namibian Constitution (1990) (Article 15) offers some promise for a constructive law reform process.

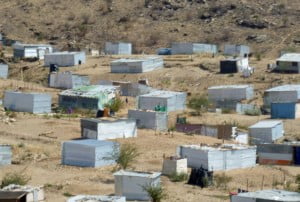

As much of the Namibian population is essentially rural, the government has established mobile teams to educate, service, and provide support for young persons throughout the country. Admittedly, there are fewer than 90 social workers to service the entire country, but, based on available data, juvenile delinquency is not a serious problem. However, it may arguably be a growing concern in such cities as Windhoek where people from the rural areas are migrating with the hope of finding better opportunity. Once there, comparatively high rent and/or house prices dramatically limit access to even the most basic of accommodations, and hence, there are an expanding number of shanty homes. In such communities as Katatura there is no running water, no electricity, and no formal infrastructures to provide even the most basics of quality of living. Opportunities for young people are further jeopardized by the high unemployment rate in the country. Namibia also has no dedicated juvenile institution, but instead, has allocated sections of their prisons to housing juveniles. While not ideal, it is an attempt to keep young offenders separate from adults. Correctional staff are not specifically trained to work with this population and there are no specialized programs within the institutions for youth.

Finally, although there has been discussion of establishing a probation system for juveniles, it does not currently exist, even though UNICEF has provided a toolkit for establishing a probation system for sub-Saharan countries. In addition, there are, in principle, provisions for community-based programs, but again, none have been established.

In summary, during the late 1990s and early into the new millennium, Namibia seemed well on its way to creating a progressive juvenile justice system that complied with many of the international and continental African standards. However, as seems to be the case with many developing countries, those who have no voice or power do not have priority in the political arena. Namibia has much it can be proud of, but based on my experience, there is much that can and still needs to be done to ensure the rights, needs, and safety of delinquent youth in Namibia are respected. Again, as Dr. Schulz noted a few years ago: “it is high time for the role players and stakeholders in the Namibian CJS… to reinvigorate the process which had been so promising.”