For well over 100 years, students in industrial-era trade apprenticeships and professions have learned by ‘watching and doing’ under the supervision of the master craftsman. Historically, there was little or no pay or benefits associated with these tutelages. They were viewed as voluntary educational experiences which benefited the apprentice and burdened the senior craftsman.

Most trades and professions in Canada still operate today under this model of “shadowing” and learning skills by practising them under the guidance of a master. For Alberta trades, by way of example, see the Apprenticeship and Industry Training Act.

Apprenticeships and training programs that must be completed to earn full qualification have given rise to the modern internship. Not all internships are the same, but they usually involve learning about skills or business under the direction of proficient mentors.

The Modern Unregulated Internship

In recent decades, enterprising students, graduates and others – in the belief that industry contacts and practical experience enhance their employability – volunteer to work as unpaid (or under-paid) interns in private and public sector organizations. These are usually short (less than one year) term positions. The experience varies considerably in each internship. But since it is not a regulated academic requirement for any formal program, some of the ‘work experience’ will be routine work that regular employers at the organization can perform.

Organizations are willing to accept interns for several reasons:

- They want to assist them by giving them an inside view of their industry and business.

- They incur some overhead cost in hosting the intern, but they receive some service in return.

- Each side is able to assess the other at low cost if a regular job opens up.

Since such an internship is a voluntary relationship between two consensual parties, why must the law intervene?

Each province and territory has employment standards legislation that applies to internships without actually using the word “internship”.Some Canadian legislators assume these unpaid internships are exploitative of young, inexperienced workers. Legislators stipulate minimum wages, holidays, hours between shifts and many other minimum employment standards. In the same way, they have set rules across the country to govern when internships must be converted into regular paid jobs. This article outlines the regulation of internships in Canada under employment standards legislation.

Each province and territory has employment standards legislation that applies to internships without actually using the word “internship”.

Professional Exemption

British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia exempt professional interns from employment standards legislation. Those training in the professions of law, accounting, medicine, engineering, dentistry and architecture are usually covered by some employment standards (such as minimum wage) but exempt from other standards like hours of work, statutory holidays and overtime. These trainees are not treated in law as regular employees. Professional statutes also regulate these individuals. For example, a student-at-law in Alberta is regulated by the Legal Profession Act, and an engineer–in-training is regulated by the Engineering and Geoscience Professions Act.

School Program Exemption

Interns who must work for an organization to satisfy a requirement in their formal education program come under school program exemptions. These exemptions operate everywhere in Canada except Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and the Yukon. If work experience is a program requirement of the educational program, one may be legally unpaid for work performed.

In 2013, a co-op student complained to the Ontario Labour Relations Board saying he should have been paid under section 1(2) of Ontario’s Employment Standards Act. The Board identified six conditions for this exemption (Sandu v. Brar):

- the training must be similar to that in a vocational school;

- the training must be for the benefit of the intern;

- training organizations must derive little, if any, benefit from the intern’s activities in the organization;

- the intern does not displace employees;

- the intern is not entitled to become an employee of the organization; and

- the intern must be agree there is no remuneration for the training.

Although this Ontario administrative decision – which seems to add to the legislation more than interpret it – is not binding on any tribunal beyond itself, its principles may influence other jurisdictions.

General Un-Categorized Internships

Interns who must work for an organization to satisfy a requirement in their formal education program come under school program exemptions.Many roles and positions that are called “internships” are actually regular, short, fixed-term, entry-level jobs. Most Canadian business and engineering schools permit (not require) their students to take six to eighteen months off to work in a company to learn practical aspects of their studies. The designation of ‘internship’ only relates to the temporary nature of a job that is not required for the completion of the program or certification. These gigs usually refer to a learning feature in the work but all short-term entry jobs engage learning.

In other instances, a company may have a small general internship program where the roles look like regular work but there is no compensation. It is impossible to judge all or any of these as worker exploitation as both sides seem to find value in the voluntary internship. Union officials tend to oppose these arrangements because any free labour destabilizes salaries and job levels. In response, Canadian legislators have invoked employment standards to apply to any scenario where one ‘could be paid’ for the work performed.

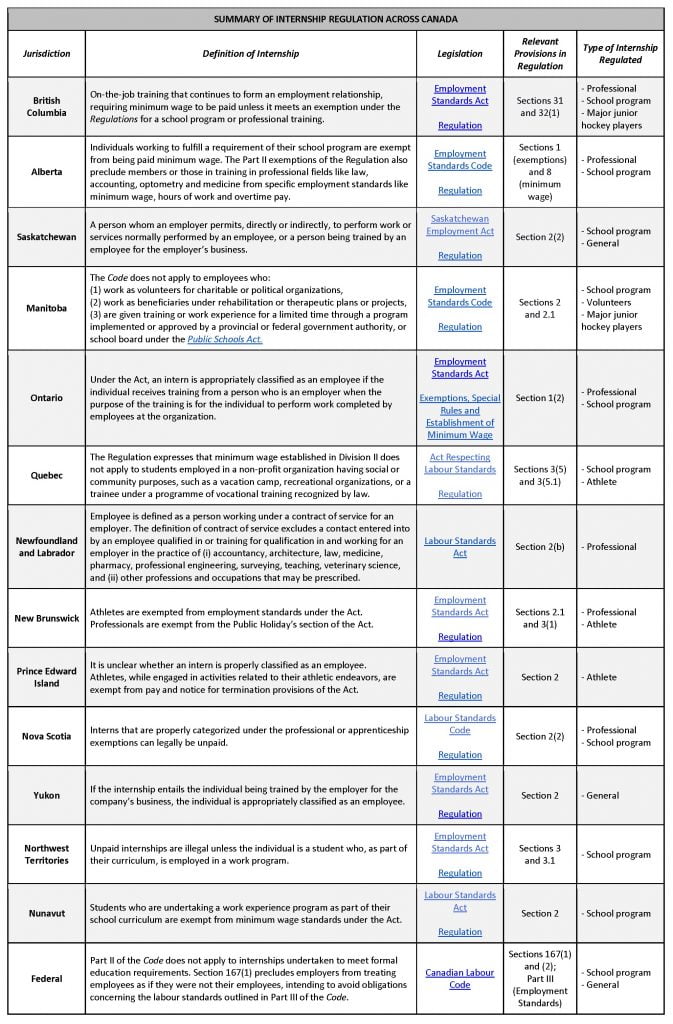

The table below (click to view larger) sets out this pertinent legislation in detail. Today, unpaid internships – depending on the specific facts – may violate employment standards legislation. Courts and provincial regulators will interpret these employment standards provisions broadly. The common law test for employment will include many interns. In 1998, the Supreme Court of Canada called for broad and generous interpretation of minimum benefits and standards legislation that protects workers (Rizzo Shoes Ltd).

Hockey Player Exemption

British Columbia, Quebec, Prince Edward Island and Manitoba exempt ice hockey players from employment standards legislation. In return, players receive an annual scholarship covering the cost of post-secondary education (including books and fees) through a contractual agreement between the player and the league.

Conclusion

Many roles and positions that are called “internships” are actually regular, short, fixed-term, entry-level jobs.An internship can mean many different things. For example, law students often take elective internships during law school (eg. working with a lawyer or judge) and must complete one year of articling after graduating. Articling is a mandatory, regulated professional internship. Almost nothing in law flows inexorably from the vague category of work known as “internship”.

The law is clear for unpaid and underpaid apprenticeships and internships in trades, professions and academic programs where a short period of practical work experience is prescribed. These arrangements are governed by vocation-specific legislation. The non-prescribed internships – those that are voluntary and ad hoc – must be evaluated on their own facts according to the employment standards legislation applicable in each jurisdiction. For example, is the learning experience such that it can be properly deemed to be ‘employment’ at all? Is it work (even in non-profit organizations) that is otherwise and generally could be remunerated (ie. does the intern take the place of a paid employee)? If so, the relationship, even with learning and training elements, must be treated as a regular paid employment. If the intern performs (and therefore, replaces) regular paid work, the intern must be paid. Non-compliant organizations may be fined and ordered to pay full salary and benefits for the entire internship period.

Finally, what is sometimes called an ‘internship’ may in law and fact be a regular, full-time, short-term job that is already employment standards compliant. It is called an internship out of mutual recognition that it is a short, fixed-term, temporary job that offers both worker and organization some value. And, in many cases, these stints provide the employee and employer an opportunity to assess each other for suitability in a longer-term employment relationship.