In my recent article, “What, Why and Where: Untangling Jurisdiction in Family Law,” I explained how litigants navigate the thicket of jurisdictional choices involved in a family law dispute. First there’s choosing the right law, because the federal and provincial governments have overlapping jurisdiction over some but not all family law problems. Then there’s choosing the right court, because in many provinces and territories there are two trial courts with overlapping jurisdiction over some but not all family law problems. … in some parts of some provinces, namely Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Ontario and Saskatchewan, there is just one court for family law disputes Making matters worse, not all courts can deal with all laws and the two trial courts usually have different rules, different processes, different forms and different fee structures.

In my recent article, “What, Why and Where: Untangling Jurisdiction in Family Law,” I explained how litigants navigate the thicket of jurisdictional choices involved in a family law dispute. First there’s choosing the right law, because the federal and provincial governments have overlapping jurisdiction over some but not all family law problems. Then there’s choosing the right court, because in many provinces and territories there are two trial courts with overlapping jurisdiction over some but not all family law problems. … in some parts of some provinces, namely Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Ontario and Saskatchewan, there is just one court for family law disputes Making matters worse, not all courts can deal with all laws and the two trial courts usually have different rules, different processes, different forms and different fee structures.

This can all be very confusing for litigants without lawyers. Frankly, it’s confusing for many lawyers as well. However, in some parts of some provinces, namely Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Ontario and Saskatchewan, there is just one court for family law disputes, a court that has the jurisdiction to deal with all family law problems and all of the laws that might apply to them. In some provinces, like Saskatchewan, government has solved the jurisdiction nightmare by simply assigning all family law disputes to a special division of the superior court. Other provinces, like Ontario, have created a special hybrid court, a “unified family court,” to deal with everything.

Despite the holdout of large, wealthy provinces such as Alberta and British Columbia, the idea of unified family courts is not a new one. Manitoba, Ontario and Saskatchewan each launched pilot projects in 1977, British Columbia initiated a short-lived project in 1974 and a committee of the Alberta Law Society recommended the establishment of a unified family court in that province in 1968. In addition to reducing public confusion by creating a one-stop shop for family law disputes, the basic premises behind the idea of unified family courts are these:

- Family law is a unique species of civil law that deals with complex problems and future-oriented problem-solving. A unified court will result in its judges developing significant specialized expertise in a difficult area of law.

- A unified court will allow all of the problems arising from the end of a relationship to be dealt with in one place, reducing the likelihood of simultaneous proceedings, litigation harassment, tactical delays, and conflicting court orders. Despite the holdout of large, wealthy provinces such as Alberta and British Columbia, the idea of unified family courts is not a new one.

- Social services related to family breakdown will be integrated more effectively and efficiently into the court system and judicial processes.

- A unified court will adapt and evolve rules specific to its needs and those of the families before it, and improve access to justice by establishing simplified forms and processes.

- A unified family court managed by a specialist bench will produce outcomes for families that are better tailored to their individual needs and circumstances.

Makes sense, doesn’t it? This is the rationale for a unified family court given in Alberta in 1976 by a special committee composed of the province’s Chief Justice, judges from the superior and provincial courts, with representatives from the Law Society of Alberta and what was then known as the Department of the Attorney General:

Family law deals with the problems of husbands and wives arising from the breakdown of marriages. It deals with problems of the protection and support of children arising from the breakdown or lack of family relationships, and the problems arising from the unlawful conduct of children and juveniles. These are among the most numerous and the most serious and important problems with which society must deal, and it is imperative that society provide strong courts and efficient social services in order to deal with them.

The Committee is concerned that the numerous and varied problems affecting families are not being satisfactorily dealt with under the present divided court structure. The fragmented jurisdiction makes improvement very difficult. The Committee is convinced that the time has come when important changes and solutions can be implemented only if a Family Court is created with original exclusive jurisdiction over the entire field of matters affecting the family.

However, despite recommendations for unified family courts made in 1968, 1972, 1976 and 1978, little progress was made toward their implementation in Alberta until 1999 when the government decided to solicit public input on a range of justice issues. A consultation paper (PDF) released subsequently stated:

One of the messages the Government received was to simplify the justice system. Delegates felt that the system created delays, discouraged access, and, in some cases, resulted in citizens being denied justice.

These messages led to the founding of the Unified Family Court Task Force in 2000, and from there, surprisingly, The complexity of the family justice system has a direct impact on the ability of litigants to proceed without counsel. to yet another recommendation to establish a unified family court in the province in 2003, followed by an actual proposal to the federal government to cooperate in its establishment. Here’s how one commentator, lawyer and academic Michelle Christopher, described the rationale for a unified family court a year later:

Access to justice has long been a concern to the public, particularly in family law disputes, where parties lack the deep pockets to provide funds to sustain the type of prolonged and costly litigation that is common in corporate and commercial law contexts. Leaving aside for the moment considerations of whether it is in fact even appropriate to litigate family law matters…

— well said! —

… it has been argued that family law litigants are at a distinct disadvantage in trying to proceed without legal counsel, because the jurisdiction for family law problems is not limited to one level of court, or in Calgary, even to one court building! The public has long complained, and with good reason, that it is difficult to know whether their matters will be heard in Provincial Court or in the Court of Queen’s Bench. …

The public is not expected to be entirely conversant with issues of legislative jurisdiction, which require federal matters such as divorce to be heard in the first instance in the Court of Queen’s Bench. The Provincial Court of Alberta has jurisdiction to hear all matters of “purely local and provincial concern,” including child welfare and domestic relations (non-divorce, guardianship, custody and access) matters relating to the children of unmarried or never-married parents, or separated parents who are not yet divorcing, except if the proceedings are to establish paternity, in which case the Court of Queen’s Bench has jurisdiction. If you are a grandparent seeking access to your grandchild, your matter will be heard in the Provincial Court. In the case of child support, matters are also heard in the Court of Queen’s Bench, unless you are bringing an application for the reciprocal enforcement of a child support order from another province, in which case you will be heard in the Provincial Court, and so on. You get the picture. Except that it’s totally confusing to members of the public, and does affect access to justice.

Although Christopher’s critique focuses somewhat more heavily on access to justice concerns, her comments are not terribly far removed from the observations the special committee made almost three decades earlier. There have, however, been three important developments in the last year or two which suggest that hope is not lost for an Alberta unified family court. Sadly, the Alberta government’s efforts came to naught, as time has since told. Family law litigants have remained plagued by the confusion and inefficiencies caused by two courts of concurrent family law jurisdiction.

The complexity of the family justice system has a direct impact on the ability of litigants to proceed without counsel. In a 2014 survey of 167 judges and family law lawyers conducted by the Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family and two prominent academics, all Alberta respondents said that special challenges always or usually arise because of unrepresented litigants’ unfamiliarity with the rules of court and the law of evidence, and 96.9 percent said that challenges always or usually arise because of litigants’ unfamiliarity with court processes.

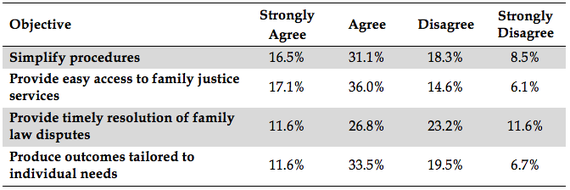

Interestingly enough, unified family courts do indeed seem to produce some of the outcomes upon which they are premised. According to a 2006 report prepared by the Research Institute and Nicholas Bala, a professor of law at Queen’s University, for the federal Department of Justice, most family law lawyers practicing in regions with unified family courts say that they have simplified court procedures, provide easy access to family justice services and produce outcomes tailored to individual needs. What they’re not so good at is providing a speedy resolution to family law disputes. This is what the 164 lawyers surveyed said about four key performance benchmarks:

There have, however, been three important developments in the last year or two which suggest that hope is not lost for an Alberta unified family court. First, the 2012 report of the Family Justice Working Group (PDF) of the national Action Committee on Access to Justice in Civil and Family Matters, recommended that each jurisdiction establish its own unified family court with:

…unified legal jurisdiction, specialized courts, simplified rules and procedures, a range of dispute resolution methods, and ancillary, integrated legal, community and social services.

The Action Committee reports have sparked, and had a profound impact upon, a number of justice reform efforts that are presently underway across Canada, including, and this is the second development, Alberta’s Reforming Family Justice Initiative. The Initiative is led by Justice Andrea Moen of the Court of Queen’s Bench and Assistant Deputy Minister Lynn Varty from Alberta Justice and aims to produce recommendations for a family justice system that is “open, responsive, cost-effective and puts the needs of children and families first, while assisting families with the early and final resolution of disputes.” If there is ever going to be an opportune time for significant change in Alberta, now would seem to be it.

Finally, the Minister of Justice, Jonathan Denis, told the Calgary Herald in January 2014 that “the government is studying” If there is ever going to be an opportune time for significant change in Alberta, now would seem to be it.— again? — “the possibility of establishing a unified family court to hear all family law matters.” This statement was followed in May by some rather unfortunate remarks from former Premier Dave Hancock that although “a unified family court would be more efficient than the existing system,” there is “a war between the Provincial Court and Court of Queen’s Bench as to who gets control.”

Thankfully, Premier Hancock’s perhaps ill-considered comments triggered statements from both Provincial Court Chief Judge Terrence Matchett and Court of Queen’s Bench Chief Justice Neil Wittmann to the effect that they both support the idea and have a “mutual willingness” to consider a unified family court. The Chief Judge told the Herald that:

I really think it’s time to reconsider the unified family court process and I think we should look at what the other jurisdictions are doing.

and the Chief Justice said:

A unified family court is on the table because everything is on the table. … A lot of the people in the public are very rightly and justifiably uncertain of what court they should come to. … It’s a disservice to the people of Alberta.

I couldn’t agree more. The Chiefs’ statements evidently resulted in some forelock-tugging on the part of the former Premier, who told the Edmonton Journal in a July interview that:

It would be more efficient if we had — I’m going to say this out loud and get in trouble — a unified family court, so that there was one court that dealt with all of the issues with respect to child, family, divorce and property. … It would be more effective and efficient, and it would be better justice.

Report after report has commented on the barriers that inhibit access to justice, and prominent among them is the labyrinthine complexity of a judicial system involving two courts with concurrent but incongruent jurisdiction, with different rules, processes and forms. This barrier assumes a new significance in light of the ever-increasing numbers of litigants involved in civil court proceedings without counsel, numbers which represent anywhere from 50% to 80% of the court docket depending on the jurisdiction you’re looking at.

A simpler, more streamlined process, with a new and heightened emphasis on integrated social services, managed by a bench of specialist judges, may not be the only or the best answer for Albertans, but it’s a concept that has proven to work elsewhere and surely deserves to be considered. It’s worth remembering that a unified family court has been recommended to the provincial government by various groups of learned lawyers and judges at least five times since 1968; perhaps now, in the present atmosphere of justice reform and crisis, is the time to pilot a unified family court in Alberta.