It can be a real challenge to figure out which court to go to when a family law problem needs to be resolved by a judge. You may need to go to a court where you live, or a court somewhere else. If you are going to a court where you live, you’ll have to decide which of the three levels of court you should be going to.

It can be a real challenge to figure out which court to go to when a family law problem needs to be resolved by a judge. You may need to go to a court where you live, or a court somewhere else. If you are going to a court where you live, you’ll have to decide which of the three levels of court you should be going to.

The answer depends:

- partly on which legal issues you’re dealing with,

- partly on where everyone lives and where everything is located, and

- partly on whether you are starting or replying to a claim,

and all of these issues are about jurisdiction.

“Jurisdiction” means a lot of different things but basically refers to the court’s ability to make orders resolving a particular legal dispute, and unfortunately, there are plenty of reasons why a court might or might not be able to deal with a legal problem.

First, I need to explain the structure of our court system.

There are two trial courts and one appeal court in each of Canada’s provinces. A “trial court” is a court that makes orders about legal claims, after hearing the evidence of witnesses and the legal arguments of the parties to the dispute. The two trial courts are the provincial court and the superior trial court, and the superior court has different names depending on the province. …provincial courts are often extremely busy and usually have heavier caseloads than superior courts. (In British Columbia, the superior court is the Supreme Court; in Alberta and Manitoba, it’s known as the Court of Queen’s Bench; in Ontario, it’s the Superior Court of Justice.) An “appeal court” is a court that deals with legal challenges about the outcome of a trial; these courts hear arguments but no evidence.

The provincial court is the lowest level of court and is established by the government of each province. Its jurisdiction is limited because it can only deal with the legal problems that are assigned to it by legislation. However, provincial courts are often extremely busy and usually have heavier caseloads than superior courts.

The superior trial court is a higher level of court and is established by section 96 of the Constitution Act, 1867. The federal government is responsible for appointing superior court judges, and for paying their salaries. This court has “inherent jurisdiction,” which means that it can deal with all legal problems and can make whatever orders are necessary and just, whether there’s a specific law that says they can make those orders or not. In addition to dealing with trials, the superior trial court also hears appeals from the provincial court.

The court of appeal is the highest level of court in each province. It too is a superior court Above the courts of appeal is the Supreme Court of Canada, an appeal court shared by all of Canada. that is established by the Constitution, staffed by the federal government and has inherent jurisdiction. The court of appeal only hears appeals, usually just from the superior trial court.

Above the courts of appeal is the Supreme Court of Canada, an appeal court shared by all of Canada. The Supreme Court hears appeals and references from the federal government. (A “reference” is a legal question that the government needs answered; the last reference involved the terms on which Quebec can leave Canada.) Although the Supreme Court must hear appeals in certain kinds of criminal cases, other cases must get permission to go to that court; appeals in family law cases are rarely heard by the Supreme Court.

As if this wasn’t complicated enough, there’s also the federal court system, a system that works parallel to the provinces’ superior courts and deals with legal problems like taxes, immigration claims and claims against the federal government. Trials are heard by the Federal Court, which can be appealed to the Federal Court of Appeal, which in turn can be appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada. The federal court can hear family law cases, but only when married spouses each start a claim under the Divorce Act on the same day.

Now I need to explain about the laws the federal government can make and those that only the provincial governments can make.

In addition to setting up the superior courts, the Constitution Act, 1867 also divides the powers and responsibilities involved in running a country between the federal government and the provincial governments. Under section 91, the federal government is able to make laws about things like shipping, money, Canada’s first nations and the postal service, as well as “marriage and divorce.” Under section 92, the provinces can make laws about things like railways, taverns, hospitals and logging, as well as “property and civil rights” and “all matters of a merely local or private nature.” As a result, both levels of government can make laws about family breakdown.

Since only the federal government can make laws about divorce, we have the federal Divorce Act. Alberta’s Family Law Act and Matrimonial Property Act are a lot different than British Columbia’s Family Law Act or Saskatchewan’s Children’s Law Act and Family Property Act. This law sets out the rules for how married people get divorced, and, for married people, talks about the care of children after separation, child support and spousal support.

Since only the provincial governments can make laws about property and civil rights and “matters of a private nature,” we have provincial laws that make rules about how property is divided, the care of children before and after separation, child support and spousal support, and sometimes about parental support and the rights of family members like grandparents. However, because each province can make rules about these subjects, the rules change from province to province, sometimes quite significantly. Alberta’s Family Law Act and Matrimonial Property Act are a lot different than British Columbia’s Family Law Act or Saskatchewan’s Children’s Law Act and Family Property Act.

Making things a bit more complicated, in most provinces only the superior courts have the jurisdiction to deal with family law claims under the Divorce Act and the unwritten rules of the common law. Although both courts can deal with claims under the provincial legislation, the provincial courts generally can’t deal with claims about protecting or dividing property.

Finally, I need to explain about the geographic limits of jurisdiction.

As a general rule, the courts of one province won’t deal with legal claims involving people or things located in another province or in another country. There are, as you’d probably expect, lots of exceptions to this rule.

Under the Divorce Act, you can start a claim for divorce in the province where you normally live or in the province where your spouse normally lives, as long as you or your spouse have lived in that province for at least one year. Most provincial laws don’t have rules about jurisdiction like the Divorce Act. In general, the court will let you start a claim involving someone living outside your province as long as there is a connection between you, your relationship or the other party and your province. However, if there is a claim for custody of a child, the court can move the claim to the province where the child has the most ties.

Most provincial laws don’t have rules about jurisdiction like the Divorce Act. In general, the court will let you start a claim involving someone living outside your province as long as there is a connection between you, your relationship or the other party and your province. In other words, the court of Alberta may not want to hear a claim involving a relationship you left in New Brunswick; the court in Alberta may say that it’s better for the New Brunswick court to hear the claim. The rules about property claims are usually more specific: the court of one province can hear claims about movable property (bank accounts, cars, equipment and so on) located in another province, but usually won’t hear claims about immovable property (real estate) located in another province.

Most superior trial courts have rules about when you can start a claim against someone who lives in another province or another country; most of the time you can just go ahead and start the claim, but some courts may ask you to get permission before you serve the other person. The court will not hear your claim unless the other person has been served.

Provincial courts generally won’t let you serve someone who lives outside the province. A few courts, like the Provincial Court of British Columbia, allow service outside the province, but on certain conditions.

Now that we’ve gone through all of this, let’s go back to the question that started this article. Which court should you go to and why?

This question is really only complicated for people who are starting a new claim. If you are replying to someone’s claim, you have to go to the court in which the claim was started, although you can argue that the court shouldn’t agree to hear the case, that it should “decline jurisdiction,” later. If you’ve already been through a trial and are unhappy with the result, you need to go to the superior trial court, if your trial was heard by the provincial court, or to the court of appeal, if your trial was heard by the superior court.

If you are the person starting a claim, here are some of the things you’ll want to think about in deciding which court to go to.

- Provincial courts generally charge no or very low fees. Superior courts charge fees for things like starting a claim, making an application and hearing a trial to help reduce their operating costs.

- The rules and forms of the provincial courts are usually relatively short and usually written in relatively straightforward language. The rules and forms of the superior courts can be extremely complicated and difficult to understand; law schools have a course called Civil Procedure just to help students understand the rules of court!

- Provincial courts are designed for people who don’t have lawyers; the judges and courts clerks expect people not to have a lawyer, try to keep things as simple as possible and will often overlook minor problems with the rules. Superior courts tend to be more rigid with their rules and have high expectations for people involved in a claim.

- Only superior courts can deal with claims under the Divorce Act or relating to property, and only superior courts have the inherent jurisdiction to make orders as necessary, whether there’s a specific law that says they can make those orders or not.

- There are generally a lot more locations for the provincial court than there are for the superior courts, especially in rural and remote areas of the country.

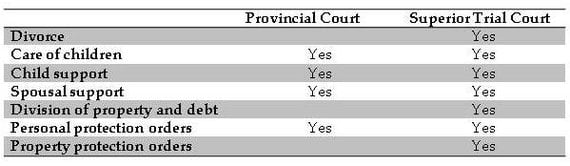

Here’s a summary chart that shows with sorts of issues the provincial courts can deal with and which only the superior courts can handle. If you don’t need to go to the superior trial court, the provincial court may be your best bet, especially if you’re not going to hire a lawyer.

One last thing needs to be said. You can start a claim in provincial court about some of your legal problems and start a claim in the superior trial court later to deal with the rest. This is fairly common – people often run to provincial court first because of convenience and cost and later find themselves having to start a separate claim to deal with issues about property and divorce – but should be avoided if possible. If you know that you have issues that only superior trial court can deal with, it’s usually easiest to do everything all in that one place rather than having to worry about two separate court claims, two separate sets of court forms, two sets of court rules and obligations to provide information that probably overlap.