You have volunteered to give something back to your community. You have been appointed to the board of your favourite charity and you feel rightly proud that you are making a contribution of your time and support to a worthy organization. You attend your first board meeting but to your surprise, the first item on the agenda for discussion is a letter from a lawyer indicating an intention to sue the directors of your organization on behalf of his client. The suit is for unspecified damages arising from some loss alleged to have occurred during some involvement with the organization. It never entered your mind that volunteering could attract civil liability. Now you are wondering what did you get yourself into? You may even be asking if you can get yourself out.

You have volunteered to give something back to your community. You have been appointed to the board of your favourite charity and you feel rightly proud that you are making a contribution of your time and support to a worthy organization. You attend your first board meeting but to your surprise, the first item on the agenda for discussion is a letter from a lawyer indicating an intention to sue the directors of your organization on behalf of his client. The suit is for unspecified damages arising from some loss alleged to have occurred during some involvement with the organization. It never entered your mind that volunteering could attract civil liability. Now you are wondering what did you get yourself into? You may even be asking if you can get yourself out.

The real issue you are grappling with is the potential for liability and how to minimize it. To address this task, you must understand the organization and its legal structure; you must identify and avoid conflicts of interest; you must understand the strategy for governing the organization, and participate in the decision making. You will want to find answers for the following questions:

- As a volunteer director or officer, what are the chances that you could be sued?

- What are the chances that you could be made liable for your acts or conduct ?

- What are the chances that you might need insurance to protect you against the risk of personal financial loss if you are sued, whether the lawsuit is successful or unsuccessful?

- What are the important considerations you should have in mind as you proceed to complete your term as director or officer?

As a volunteer director or officer, what are the chances that you could be sued?

In simpler times only a few decades ago, suits against directors and officers of charities, non-profit organizations, and volunteer groups were rare. Those who did volunteer were considered immune from the slings and arrows of those who operated in the corporate business world. Now lawsuits in this area are increasing, whether because more persons with an injury or complaint think to consult a lawyer; because more lawyers are prepared to instigate a suit, or people believe that insurance may be in place or because some assets of individuals may be available to satisfy judgments. Some lawsuits may have no merit, but you have little control over who sues, whether the suit can be pursued in the absence of real merit, and whether the amount claimed is large or small.

What are the chances that you could be made liable for your acts or conduct?

An effective board of directors and officers is the most likely to be able to control these chances, protecting themselves and other volunteers. The legal duties of directors and officers arise when conducting the business of the organization.

First, you owe a fiduciary duty (a duty of utmost good faith) to the organization. This means you must act in good faith, honestly, loyally, diligently, prudently, and in the best interest of the organization rather than in your own self- interest. You must avoid conflicts of interest with the organization. Unless your organization is governed by a provincial statute that prescribes a special standard of care, you will be held to the subjective common standard applicable to charitable directors which may be equivalent to that of a trustee.

It is important for volunteer directors or officers to understand the legal duties they owe to the organizations they serve because the failure to execute these duties gives rise to the potential for personal liability. For example, directors are responsible for their own acts or omissions while in office. If you breach your fiduciary duty, you will be personally liable. In this context, there is no difference between the common law fiduciary obligations of profit or non-profit organization directors. You must always disclose the entire truth in your dealings with the organization and subordinate your personal interest to the best interest of the organization.

Liability does not depend on the director’s intentions, good or bad. If you allow your personal interests to conflict with those of the organization, a breach of duty of loyalty is the result regardless of your intentions. Thus, you must not have an interest that possibly conflicts with the interests of those you are bound to protect. You are not allowed to gain or profit from the fiduciary relationship to the organization.

Thus while it is clear that a director should not reap a profit at the company’s expense, it has also been held by the Supreme Court of Canada that a director should not use her or his position to make a profit even if it is not open to the organization to participate in the decision. In determining whether a conflict exists, a court will look at several factors, including the following:

- the position or office held;

- the nature of the corporate opportunity;

- its rightness;

- its specificness and the director’s or officer’s relation to it;

- the amount of knowledge possessed;

- the circumstances in which it was obtained;

- whether it was special or private;

- the factor of time in the continuation of fiduciary duty in those situations where the alleged breach occurs after the director or officer’s relationship with the organization has ended; and

- circumstances under which the relationship was terminated, whether retirement, resignation, or discharge. (Canadian Aero Service Limited v. O’Malley,1974)

Directors are encouraged to avoid holding any personal interest in a contract of the organization. This is particularly so in the case of a charitable organization.

In non-profit organizations, it is often considered that you may have a personal interest in a contract that is being entered into by the organization provided you declare the interest at the board meeting where the contract is considered and refrain from voting or influencing the voting.

Directors also owe a duty of diligence to the organization. You must act with sound and practical judgment in the best interest of the organization by attending meetings and informing yourself of the relevant aspects of issues affecting the organization. While you may delegate tasks to committees, it is prudent to maintain a supervisory function. You should also be prudent in deciding when to seek outside professional assistance and counsel. You must act within and not beyond the scope of your authority and must not direct the organization to carry out activities that are not permitted by the organization’s objects.

Directors are obliged to remit income tax and other payroll deductions as set out under the Income Tax Act; you are responsible for unpaid wages and vacation pay; and you must adhere to provincial labour standards legislation and the Canada Labour Code. As a director, you can be exposed to liability if you act beyond the scope of authority set out in the organization’s objects.

Unfortunately, the potential liabilities or standards of care depend on the facts of each situation. Preventing problems is the best method to reduce the risk of potential liability.

What are the chances that you might need insurance to protect you against the risk of personal financial loss if you are sued, whether the lawsuit is successful or unsuccessful?

There is no way to accurately assess these chances. Insurers report that most charities do not have directors’ and officers’ liability coverage. On the other hand, many insurance lawyers, risk managers, and vendors of directors’ and officers’ liability insurance recommend that such coverage be obtained. The reasons are that society has become more litigious, because some organizations do not have sufficient assets or insurance to cover losses that may occur, and also because directors are more aware about potential legal risk to the director’s own net worth and are not comfortable sitting on a board unless such insurance protection is in place.

Some organizations simply find they cannot afford insurance, or they consider it inappropriate to use the assets of the charity for the purchase of insurance.

Others find that some of their activities are such that they cannot locate insurance in the market that fits their particular needs. Some organizations are self-insured. This means that the organization agrees in writing to indemnify its directors or officers; that is, to pay any damages that are associated with directorship.

If the organization has only limited assets, it may consider it necessary to purchase directors’ and officers’ liability insurance. Others assess the risk on the basis of the number of professional staff it has. Still others consider what would be the effect of allocating large sums of money to pay for legal fees to defend such a suit. Would it require other programs to be discontinued?

It is important to note that indemnification whether it is from the organization through self insurance or from an insurance policy will not apply if the director or officer acted with wilful neglect or default.

What are the important considerations you should have in mind as you begin your term as director or officer?

You should familiarize yourself with the structure of the organization you have agreed to serve. You should read the constitution and by-laws which should set out its objects. You should ask yourself then and again during your term whether the activities of the organization always appear to be in accord with the objects.

You should ask about the operating rules: for example, what constitutes a quorum for directors meetings; what the election terms are; how board members are elected and by whom; what are the directors’ duties and responsibilities; and what is the relationship between the Chief Executive Officer and the Board. You should ensure that you understand the chain of responsibilities, the duties and liabilities of the members, officers, and directors.

Policies and procedures should be documented and distributed to directors and officers. Consider whether your board has procedures to protect the beneficiaries of your organization. For example, are there monitoring protocols in place for services and the information your organization provides? These policies and procedures should also be reviewed regularly. Whether they are to be changed or maintained, the members of the Board must make informed choices about the decisions made.

If the question arises about whether to self insure or buy directors’ and officers’ liability insurance, you must consider whether it is justified to apply charitable property to the purchase of personal insurance for directors. If your organization is not a direct service provider, there may be less risk of liability. If it does provide direct services, the risk of a future claim may be enhanced.

If insurance is already in place, read the policy wording and find out if it covers the kinds of activities your organization engages in. For example, directors’ and officers’ policies usually do not cover liability for failure to remit taxes, CCP, UI, or GST. They usually exclude coverage for property damage and bodily injury. They might exclude libel and slander. They usually apply only when a person is acting in her or his position as a director or officer of the corporation.

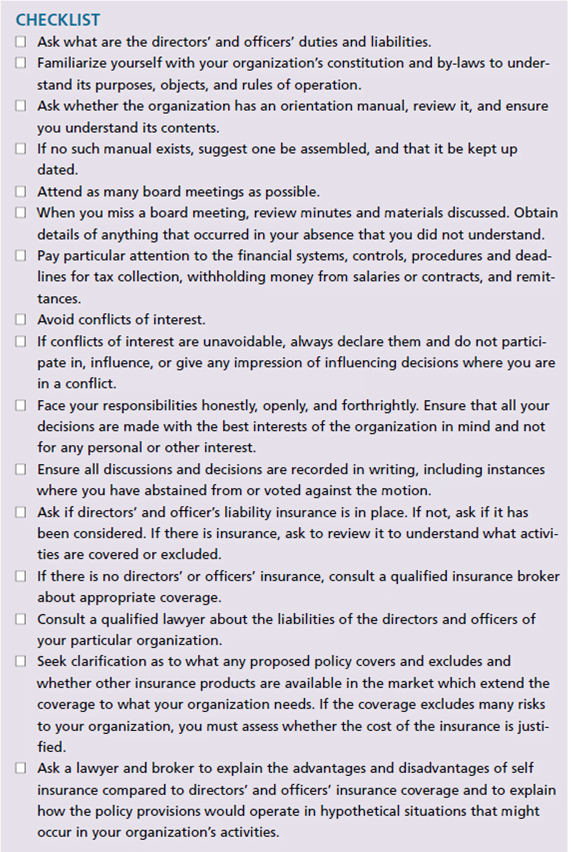

Here is a trouble shooting checklist that may be helpful to review from time to time during the course of your tenure as a director or officer. But note: it is not exhaustive.