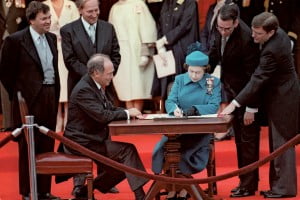

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Charter has had a significant impact on our governments and courts and it is a part of our Constitution. How does the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter), the Constitution Act, 1982, Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11, relate to our current Constitution, the Constitution Act, 1867, 30 & 31 Victoria c 3 (UK)?

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Charter has had a significant impact on our governments and courts and it is a part of our Constitution. How does the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter), the Constitution Act, 1982, Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11, relate to our current Constitution, the Constitution Act, 1867, 30 & 31 Victoria c 3 (UK)?

A brief review of some events in the days leading up to the Charter follows. In January 1968, a federal-provincial first ministers’ conference was presented with a document penned by Pierre Elliott Trudeau, “A Canadian Charter of Human Rights” (P. Macklem and J. Bakan et al, Canadian Constitutional Law 4th ed Toronto: Emond Montgomery Publications Limited, 2010 at page 719 (“Macklem and Bakan”)). This document traced the historical evolution of human rights around the world, and the history of rights recognition in Canada. For example, before Canada passed the Charter, we had the Constitution Act 1867, common law principles that recognized rights, and a Canadian Bill of Rights, 1960.

The existing Constitution Act, 1867 addressed the division of law-making powers between the federal parliament and the provincial legislatures. Civil liberties and human rights in Canada were addressed by common law cases and by the Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights (Bill), though, had its limitations. It was focused only on federal legislation and could be amended by Parliament the same way any law passed by Parliament could be amended.

During the late 1960s and 1970s, Pierre Trudeau and others sought to repatriate our Constitution and add a charter of rights. Since this would affect the notion of Parliamentary supremacy, it was difficult to obtain consensus from the provinces. In June 1978, the federal government introduced Bill C-60 (the Constitutional Amendment Bill), which set out the government’s proposed constitutional changes, and included the government’s intention of giving Canada a new constitution before 1981 (Macklem and Bakan, page 729).

In 1982, Canada experienced a “constitutional renovation” (Macklem and Bakan, page 719). In addition to repatriating Canada’s Constitution, we adopted the Charter. Some viewed and currently view this adoption as very positive; others are not so sure. Some of the resistance to the Charter was based on our British heritage. At the time, Britain did not have a written constitution, let alone a document like the Charter. Their government was based on the notion of parliamentary supremacy.

The course of debate and compromise that took place in the years leading up to the repatriation of the Constitution and the passing of the Charter are the subject of an article by Rob Normey in this issue. The impact, though, of these events is significant. First, while the majority of Supreme Court of Canada constitutional cases leading up to 1982 dealt with division of powers issues (federalism), currently there are more Charter cases. Division of powers cases still have an important place, but the Charter has a very significant place in our case law.

One momentous development is that the Charter, like the rest of the Constitution, is the supreme law of Canada. In fact, the Constitution Act section 52(1) provides that any law that is inconsistent with the provisions of the Constitution is of no force or effect. In addition, the Constitution and Charter are entrenched. This means that it is difficult but not impossible to amend. Canadians can be confident that their rights will not be easily removed or changed. Before 1982, the Constitution had no amending formula; changes had to be enacted through acts of the United Kingdom’s Parliament, upon request by our federal government on behalf of the House of Commons and Senate. Under the repatriated Constitution and Charter, most amendments can be passed only if the House of Commons, the Senate and a two-thirds majority of the provincial legislatures representing at least 50% of Canada’s population adopt identical resolutions. In this way, Canadians have a direct say in the content of our Constitution and Charter. As a result of the entrenchment, people with minority interests can obtain remedies from the courts when perhaps legislators would be more responsive to majority interests (Macklem and Bakan, page 737).

The provisions of the Charter codify provisions that ensure legal safeguards for accused persons and accountability for the police (see, for example Charter ss 7 to 14 and 24(2)). Equality rights for women, the LGBT community and the disabilities community among others are addressed in Charter s 15(1). The Charter has provided linguistic rights for francophones outside of Quebec (s 23) and has strengthened aboriginal rights (Charter s 25 and Constitution Act, 1982, s 35).

The advent of the Charter has expanded the scope of judicial review in Canada. While before 1982, judges were able to rule on whether legislation was inconsistent with the Constitution, they now can also rule on whether laws are inconsistent with the provisions of the Charter.

A brief comparison of the nature of judicial review cases under the Constitution compared to those under the Charter reveals some of the changes in judicial scope. In the federalism analysis, the court is to determine whether a law was validly passed by the federal or provincial government. The court first seeks to identify the “pith and substance” or the true meaning of a challenged law. Courts will look to the purpose and effect of the law, by looking at the law itself or at extrinsic evidence (e.g., the Hansard debates during the time the law was being passed).

Next, the court seeks to characterize the law as falling under a federal or provincial head of power. Laws may be found valid even if they have an incidental effect on a law that is within the other jurisdiction’s authority. Sometimes laws are valid under both federal and provincial jurisdictions, because they deal with differing aspects of the same matter. This is called the dual aspect principle. If there is a conflict between the two provisions, the Constitution sometimes provides which jurisdiction’s law is paramount, or, if the Constitution is silent on the matter, the federal law will prevail. A newer form of analysis examines whether a law impairs the core of a federal or provincial undertaking. If so, that law is inapplicable to the undertaking (this is called the interjurisdictional immunity principle).

On the other hand, Charter review requires a two-stage process. First, the court determines whether the challenged law infringes a Charter right. The court must characterize the challenged law (its purpose or effect) and then must define the meaning of the right. Then, the court must determine whether the right has been violated. Often, it is the effect of the law that actually indicates a violation of the Charter right. Second, the court must examine whether the law may be saved by Charter section 1. Under this stage, the government must demonstrate whether the law is demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. The court examines whether the challenged law’s objective is pressing and substantial, and whether the means chosen are reasonable and demonstrably justified (e.g., they are not arbitrary or unfair) or proportional (i.e., does the benefit gained from the law outweigh the seriousness of the law’s infringement on the Charter right?). If there is a conflict between rights under the Charter, it is largely silent about which right is to prevail. Sometimes the conflict is resolved by way of Charter section 1 (justification) and in other cases, the court tries to find ways to have the rights mutually modify each other or be harmonized.

The Charter is believed to have expanded the scope of judicial review because Charter provisions are quite heavily policy laden (Peter Hogg, Constitutional Law of Canada, Student Ed. Toronto: Thomson Reuters Canada Limited, 2011 page 36-5 (“Hogg”)). Many of the terms in the Charter are vague and may come into conflict with other Canadian values, thus requiring judicial interpretation and balancing (Hogg, pages 36-5 to 36-6). While some have criticized this development as resulting in judicial activism, in reality the Charter contains provisions that create a balance with legislative objectives: sections 1 and 33 (Hogg, page 36-9). Thus, the Charter provides opportunities for the legislative branch of Canada to offset the judicial branch and vice-versa.

Even where the court has found that the government has violated a Canadian’s Charter right, the government has the opportunity under Charter section 1 to defend its law or action as being reasonable and demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. If the court finds the violation “has been saved by Charter section 1”, the law is upheld as reflecting an appropriate compromise between an individual’s rights and societal values. Various studies have calculated that in as many as 40% of the cases, the government’s violation of a right is actually saved by section 1 (see, for example, S. Choudhry and C. Hunter “Measuring Judicial Activism on the Supreme Court of Canada: A Comment on Newfoundland (Treasury Board) v NAPE” (2003) 48 McGill Law Journal 525 at pages 548 to 9).

The Charter as a whole, and particularly Charter sections 1 and s 33 (the notwithstanding clause), provide the opportunity for dialogue between the legislative and judicial branches. This is demonstrated by the option available to the legislative branch to revise laws in a manner consistent with the Charter, when those laws are found by the courts to be in violation of the Charter, and unable to be saved by section 1. It is not unusual that the revised law will be tested in a subsequent case and found to be consistent with the Charter.

Alternatively, legislatures can use the notwithstanding clause (section 33) to indicate that the law operates notwithstanding the Charter. While some people were concerned that this clause effectively gives too much power to Parliament and the provincial legislatures to override Charter rights, in practice, the political cost of using the notwithstanding clause has kept the various governments in check.

The advent of the Charter has ensured that individual rights are entrenched in Canada. It may have expanded the role of judges, but it has also increased the dialogue between the legislative and judicial branches of government. It has certainly also raised public awareness of the courts, rights and the law.